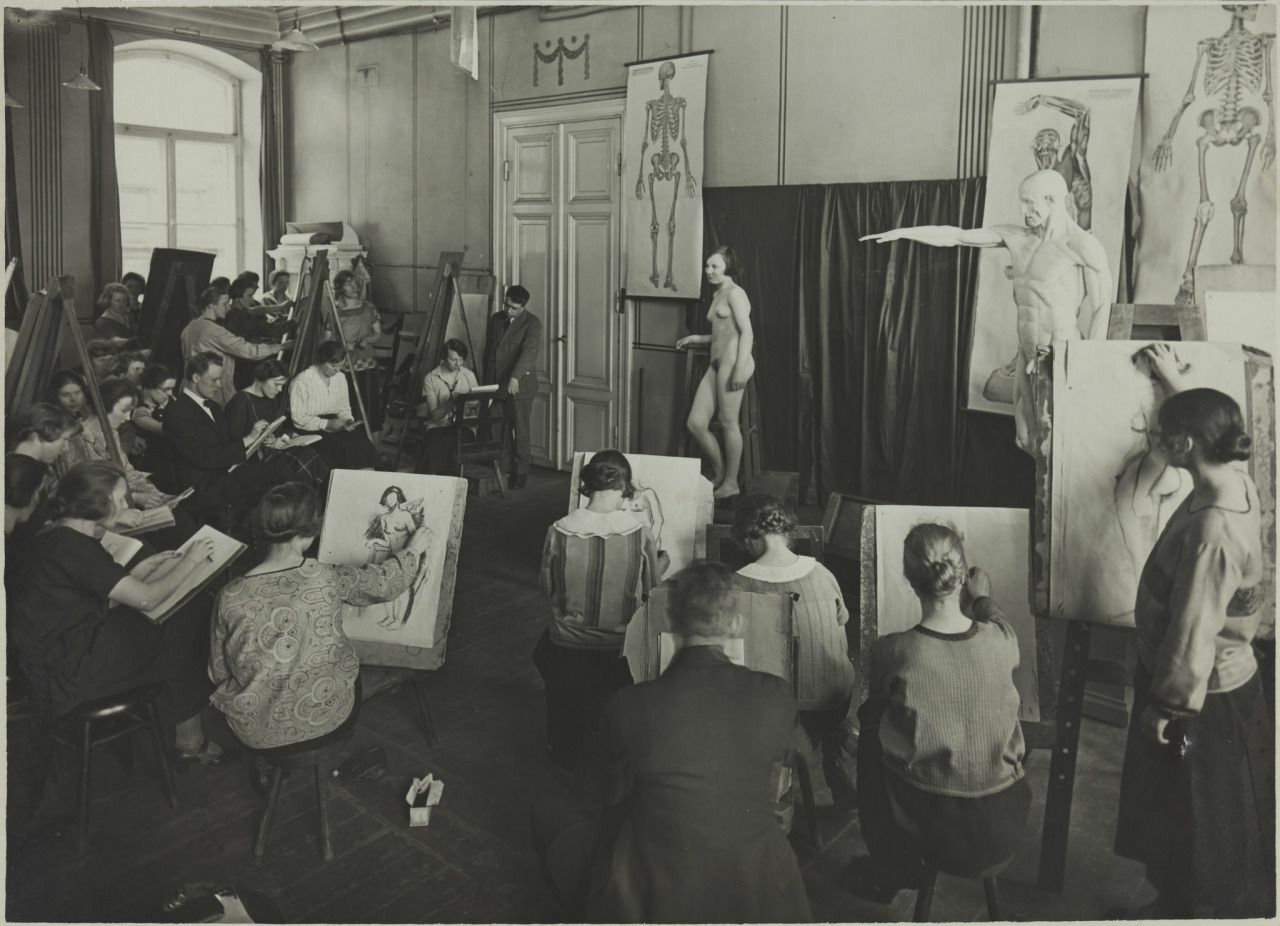

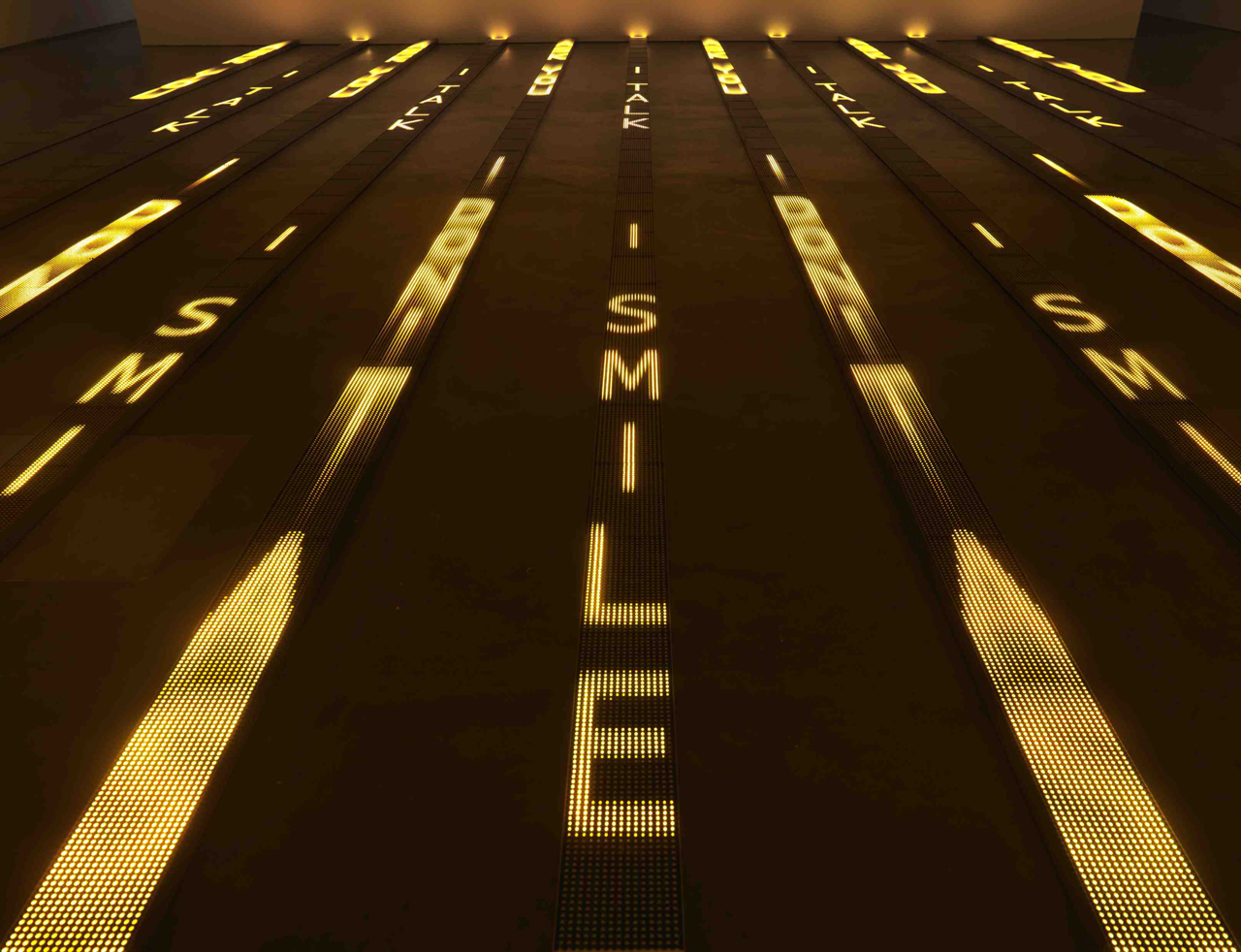

The arrangement of the installation resembles a live figure drawing session. During this activity, the object of attention is often a nude body in the center, surrounded by others. The body is exposed and platformed to be studied and observed—even dissected.

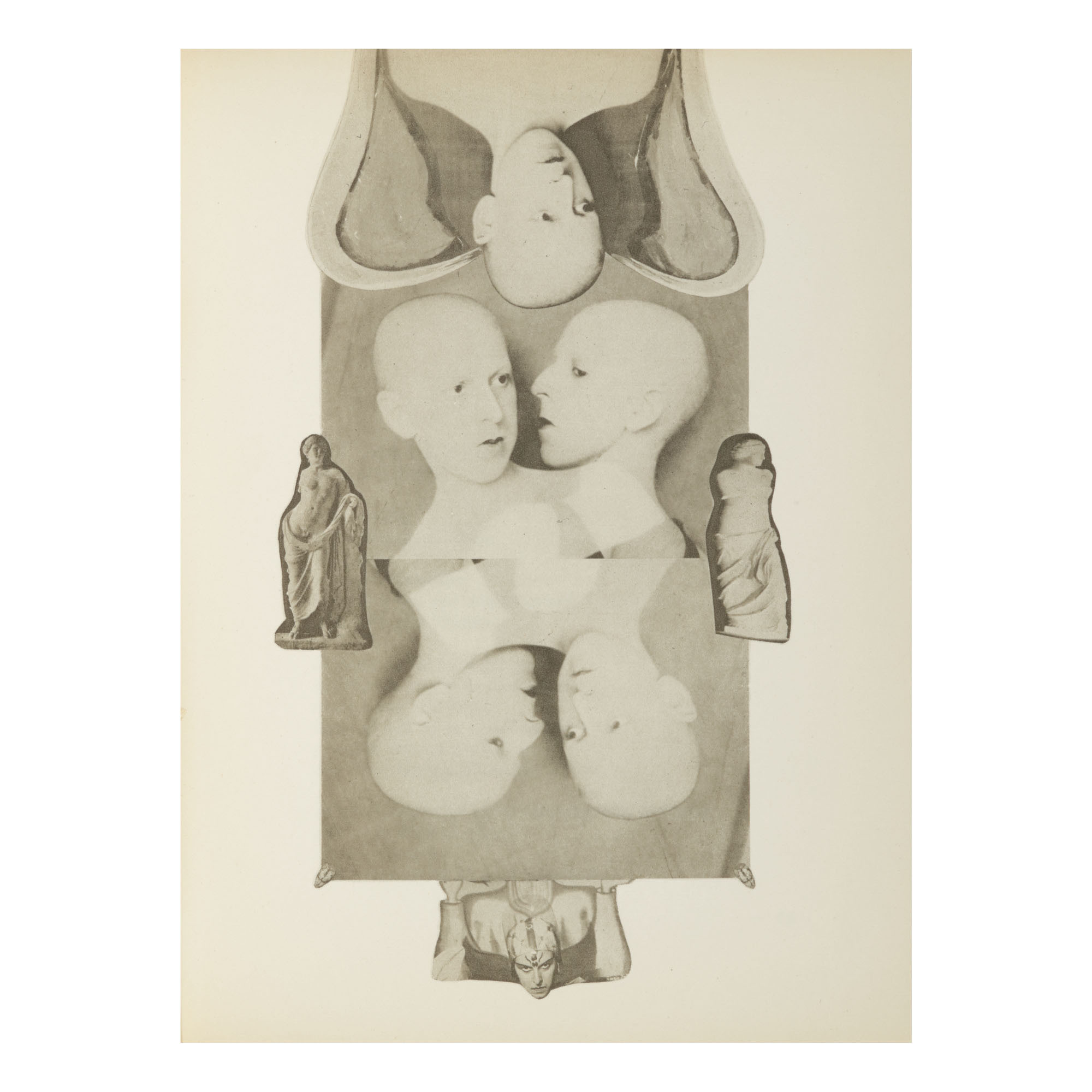

A nude body is different from a naked body. The body feels naked not merely for its lack of clothes, but because there exists a spectator who witnesses the body being naked. A nude is the perception of this naked body, and requires the spectator to see it as an object—“most particularly an object of vision: a sight.” [7] The body performs and allures when it is naked to satisfy his gaze without challenging it [8]. For the spectator, it becomes a nude—when the body learns that the way it appears affects the way it is treated, it learns to survey itself and adjust accordingly to protect its nakedness.

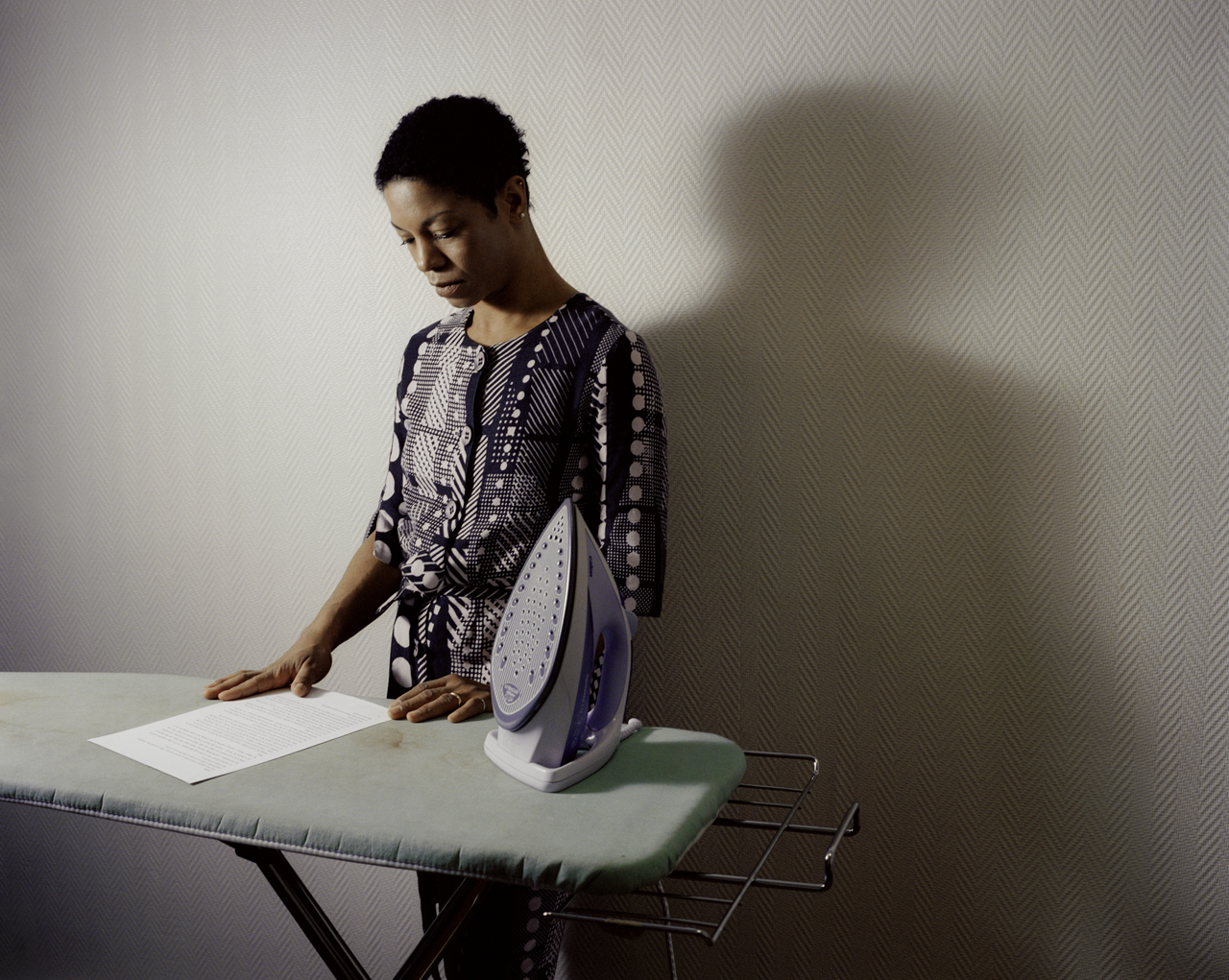

In this context, the beholder and beheld are merged with the replacement of the paper canvas by mirrors, while at the same time facing inward to reflect the gaze right back at the observers. The subversion of expectations makes one feel caught off-guard and unprepared—the first moment of nakedness—while also feeling the presence of other gazes. All resulting portraits can be arguably recognized as nudes—the self that’s been cloaked with a form of dress—by both the gaze transforming it, and itself transforming for the gaze.

This effect is amplified when we further consider another structure evoked by the installation’s form: a panopticon [9]. The surveillance principle of the panopticon requires two elements: a central monitoring figure and the monitored subjects—the “guard” and the “prisoners.” Traditionally, the guard remains invisible and can watch every monitored subject at once in the center. Using this framework, one can extrapolate the identity of the “prisoners,” “guard,” and the “structure” itself within Grebmeier Forget’s panopticon—in this case, a society and its policing gaze on self-representation. A participant, as they look into the mirror, is painfully aware of themselves and everyone else in the room. One only catches someone watching while also watching others, hence the impulse to surveil, protect, or police one’s self-image. Finally, when the policing gaze has been internalized by every person in the room, there is no need for an actual surveilling figure—every person is capable of exercising the policing gaze, thereby automatizing the process of societal correction.

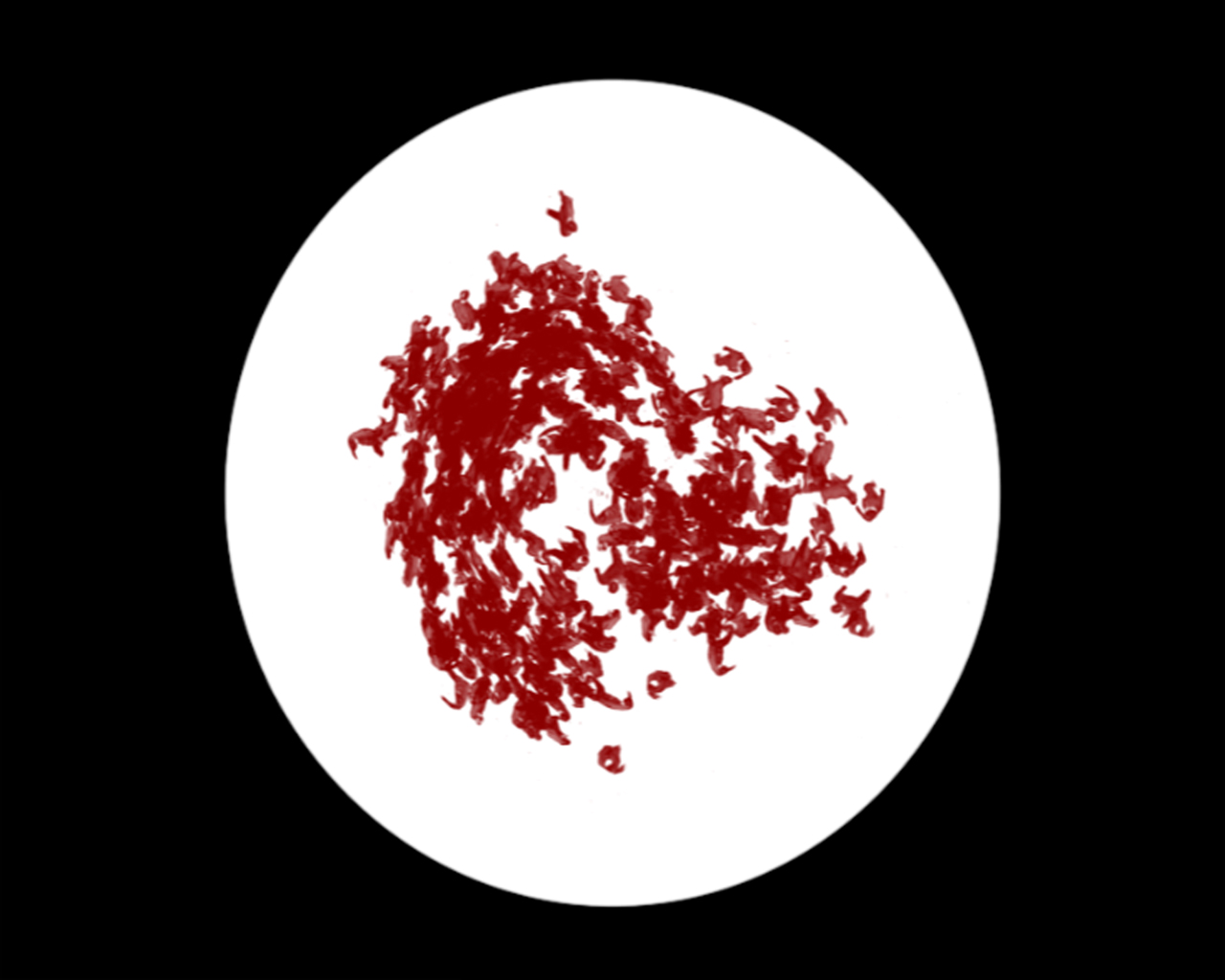

Perhaps that’s why the artist wanted to turn us into rose-tinted analog filters, to intercept our eyes so that we see differently, to shed the rigidity/confines of valid representation. Makeup is ultimately pigment, a tool that shapes a face/body into a form that is different and new. It lends its users to new modes of existence, inviting them to traverse the boundary of self/non-self (in a safe non-space), an artificial out-of-body experience. This process is sometimes constructive for the ego—through self-fragmentation, the body can learn what is part of itself, what isn’t, and what it can be. It’s the chance for oneself to be more true, when what they see outside doesn’t reflect how they feel inside. The mirror is never just itself. In Grebmeier Forget’s installation, her mirrors are windows and canvases; its participants are also canvases, looking at one another while learning to self-sculpt into shape.