[1] Isadora Neves Marques and Sofia Nunes, "Uma Entrevista com Pedro Neves Marques," in Toxicidade E Immunologia, (Lisbon: Contemporanea, 2020), 61-69. https://www.pedronevesmarques.com/texts/PNMandsofianunesContemporanea2020.pdf.

[2] It is important to highlight the differences between the terms “freedom” and “liberty,” which have been assessed in detail by media and communications scholar Wendy Hui Kyong Chun. According to Chun, liberty is bound to institutions (for example, political systems) whereas freedom is not (Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Control and Freedom: Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics, [Cambridge, MA: MIT Press]: 10). Both freedom and liberty, or the more active liberation, also differ in key ways from “emancipation,” a difference which has been elaborated greatly in decolonial theories (see, for example: Walter D Mignolo, “Delinking: The Rhetoric of Modernity, the Logic of Coloniality and the Grammar of De-coloniality,” Cultural Studies 21, no. 2 (2007): 449-514). Because Neves Marques’ works often deal with “biotechnology as a bio-political space” (Gasworks, “Interview with Pedro Neves Marques It Bites Back exhibition at Gasworks,” May 16, 2019, Video, 4:35 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f3lR40ey1qw), for the sake of this article we might consider freedom and liberty/liberation as connected (but not always interchangeable) terms. The term emancipation, however, will not be used.

[3] Informed by the political and artistic history of her family’s home country of Chile, and particularly by the socialist presidency of Salvador Allende, much of Carrasco’s curatorial work strives to imagine a utopian moment of complete liberation. “So that’s the volatility, I guess, in Aerial Skin,” she says. “There’s a notion of freedom, of being who you are in a place that welcomes it.” (Carrasco, in conversation.)

[4] Claudia Benthien, Skin: On the Cultural Border Between Self and the World (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2002): 83.

[5] Indeed, Neves Marques has cited the works of David Cronenberg as one of their key influences, particularly in the case of The Bite: Neves Marques and Nunes 2019. They also reference Cronenberg’s career in: Justin Jaeckle, “Pedro Neves Marques: Corpos Medievais,” Contemporânea, September 2021.

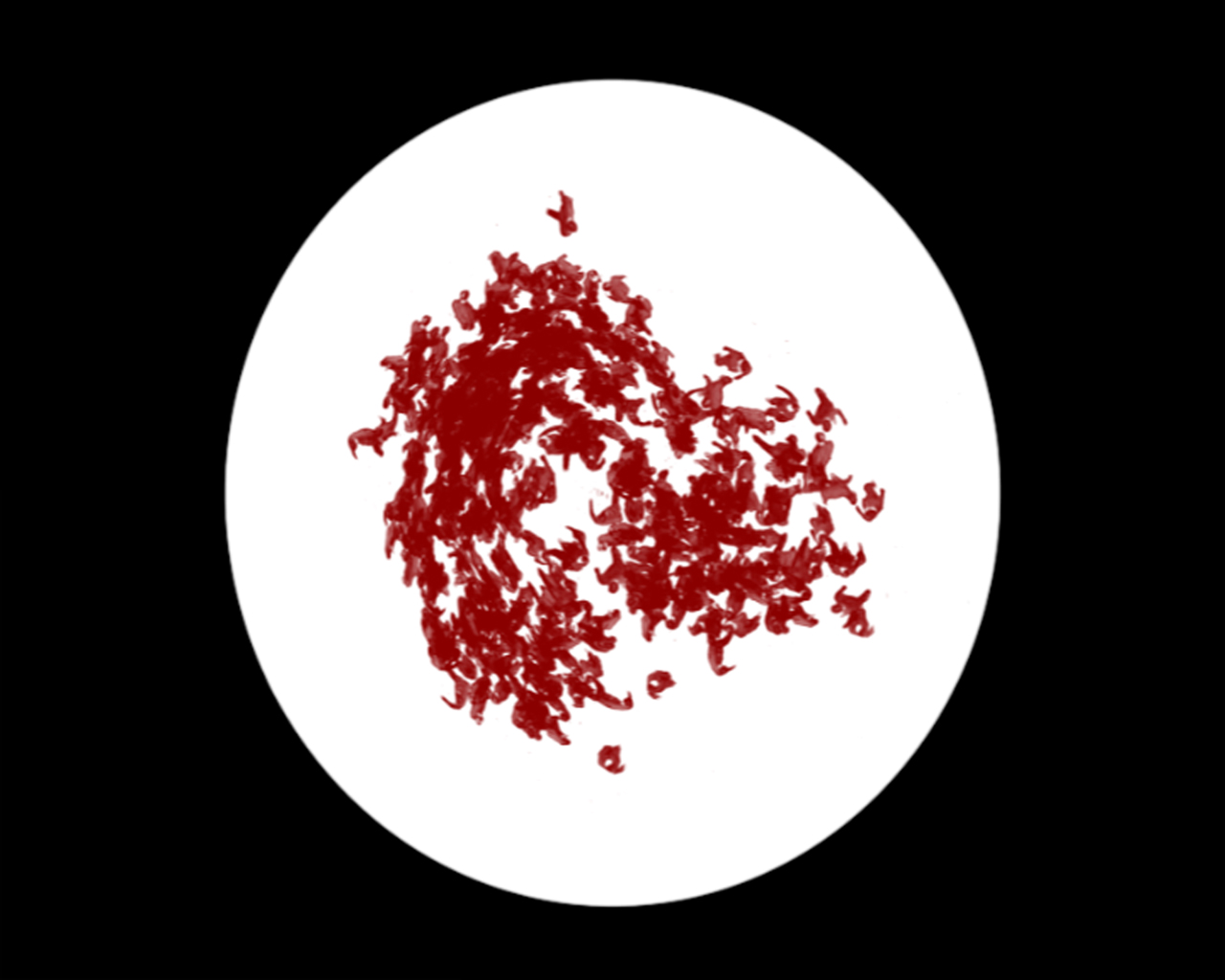

[6] While the connection between The Bite and the zika virus is not made explicit in the film itself, Neves Marques has referred to the film’s viral element as zika: Gasworks 2019, 00:30.

[7] Tao’s identity as a trans woman is never made expressly clear in the film. She is referred to as such here, then, because she is so identified in two texts linked to Marques’ website: Neves Marques and Nunes 2019 and Līga Požarska, “The Bite: Nervous Anticipations,” Talking Shorts, 2020, https://talkingshorts.com/films/the-bite?fbclid=IwAR1vZF9T6BcrPIU72jOHDf2N1LceACxiUzs-ph7PMgK6oVzERMfS_EWTUzw.

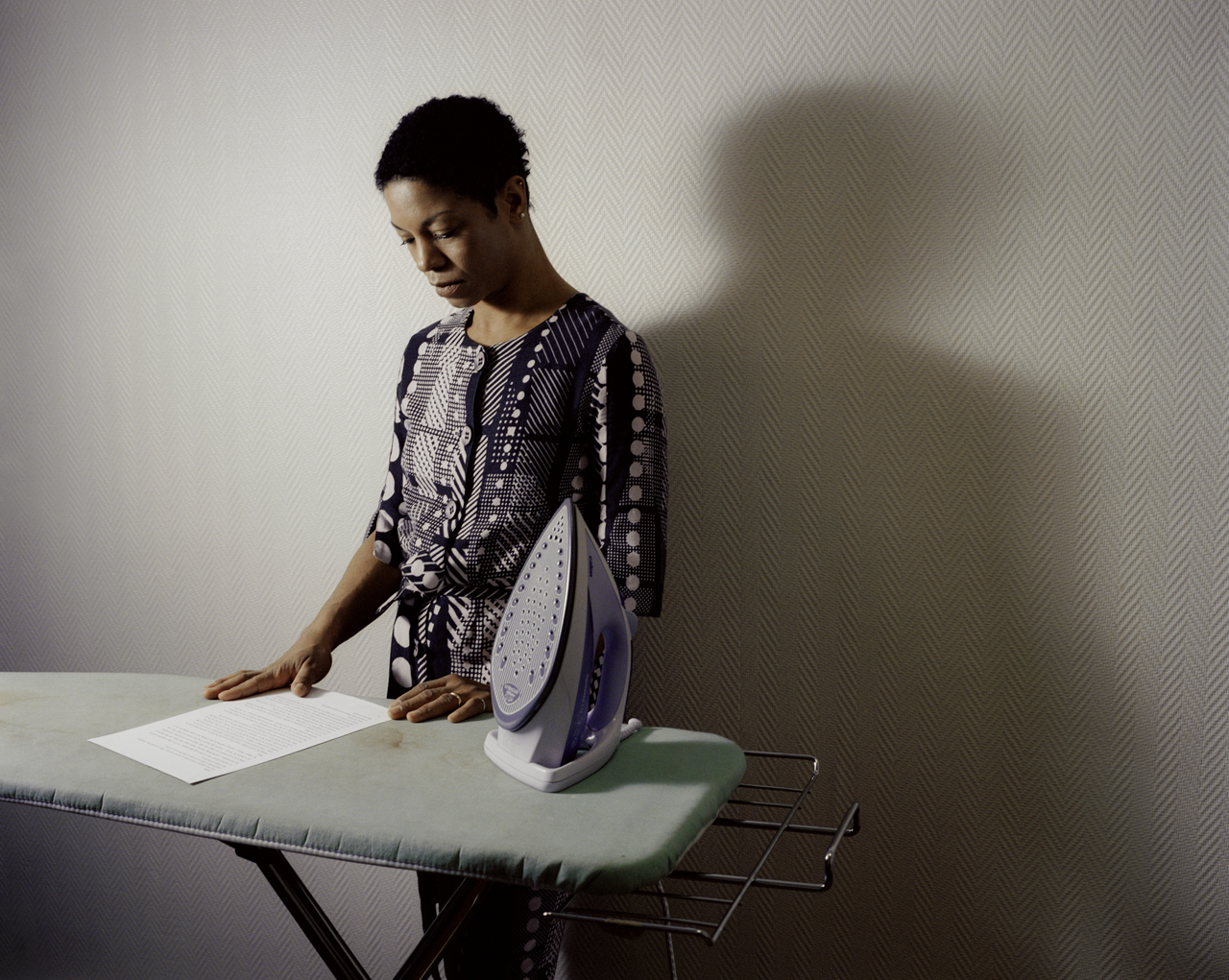

[8] Isadora Neves Marques, dir., A Mordida [The Bite] (Portugal: Portugal Films - Portuguese Film Agency, 2022) Digital, 20:10.

[9] This notion of producing parents by producing babies (and specifically the links between the biomedical production of infants and capitalist production) is explored in: Charis Thompson, Making Parents: The Ontological Choreography of Reproductive Technologies (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005).

[10] Donna Haraway, When Species Meet (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 66.

[11] Neves Marques, dir., A Mordida [The Bite], 11:45.

[12] Neves Marques and Nunes 2019; Pedro Neves Marques and Marco Antelmi, “Interview with Pedro Neves Marques,” Droste Effect, Jan 17, 2019. http://www.drosteeffectmag.com/pedro-neves-marques-interview/http://www.drosteeffectmag.com/pedro-neves-marques-interview/.

[13] Neves Marques and Antelmi 2019.

[14] The term “nature-culture” was first used in Bruno Latour’s essay “We Have Never Been Modern” (1993) to denote how “nature” and “culture” cannot exist independent of one another. Later, the words were fully combined into “natureculture” by Donna Haraway in How Like a Leaf: An Interview with Thyrza Nichols Goodeve (2000), while around the same time their co-constitutive nature was elaborated in Tim Ingold’s Perception of the Environment (2000), where it is argued that the phrase “nature is a cultural construct” is a paradox.

[15] Haraway 2007, 3.

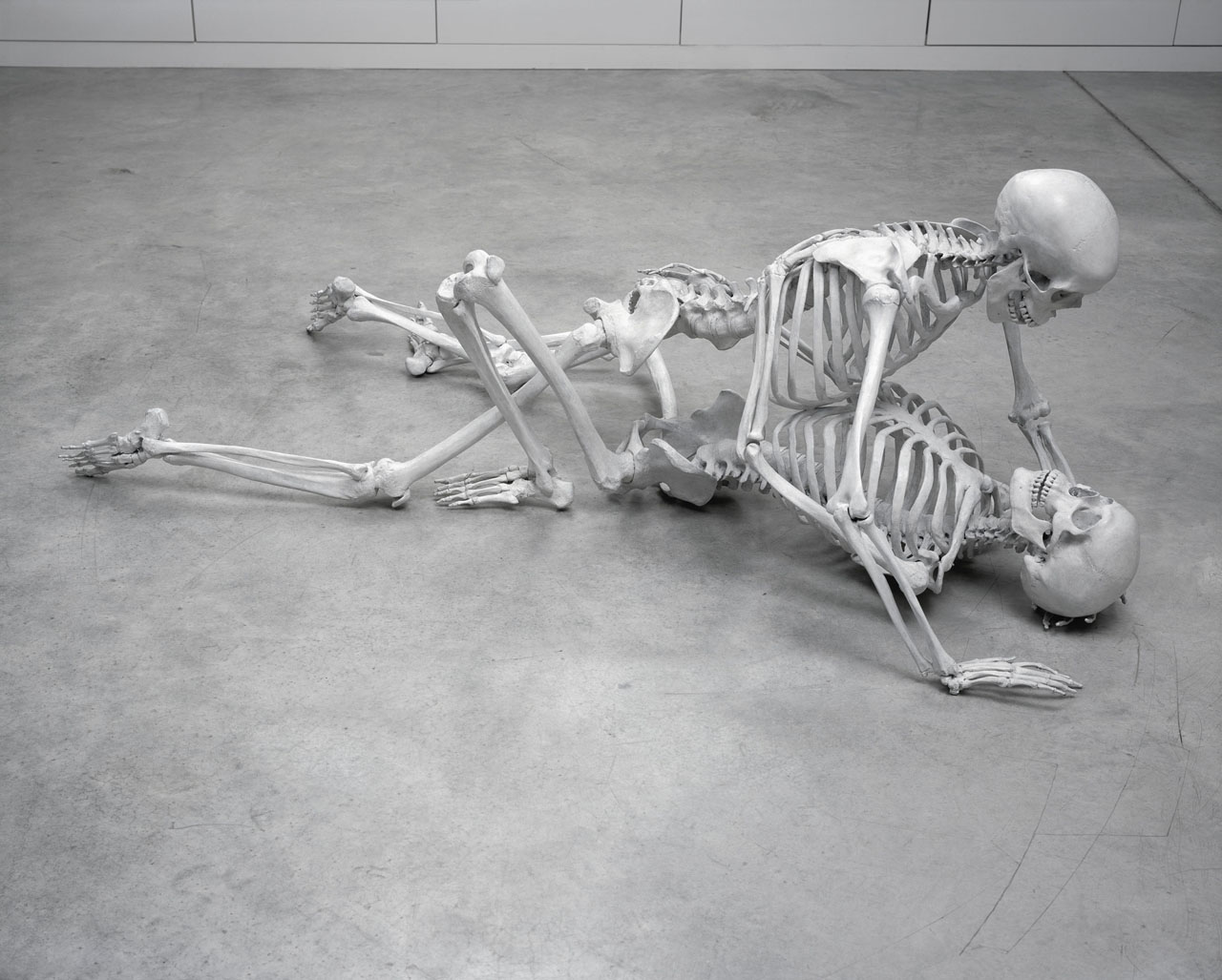

[16] Pedro Neves Marques, dir, Becoming Male in the Middle Ages (Portugal: Portugal Films - Portuguese Film Agency, 2022) Digital, 14:45.

[17] Pedro Neves Marques and Līga Požarska, “A Conversation with Pedro Neves Marques: Breaking the Norm,” Talking Shorts, Sept 2022. https://www.talkingshorts.com/interviews/breaking-the-normhttps://www.talkingshorts.com/interviews/breaking-the-norm.

[18] Marques and Požarska 2022.

[19] Pedro Neves Marques, dir., Becoming Male in the Middle Ages, 18:45.