Foundation

Marc Quinn

October 5 → January 6, 2008

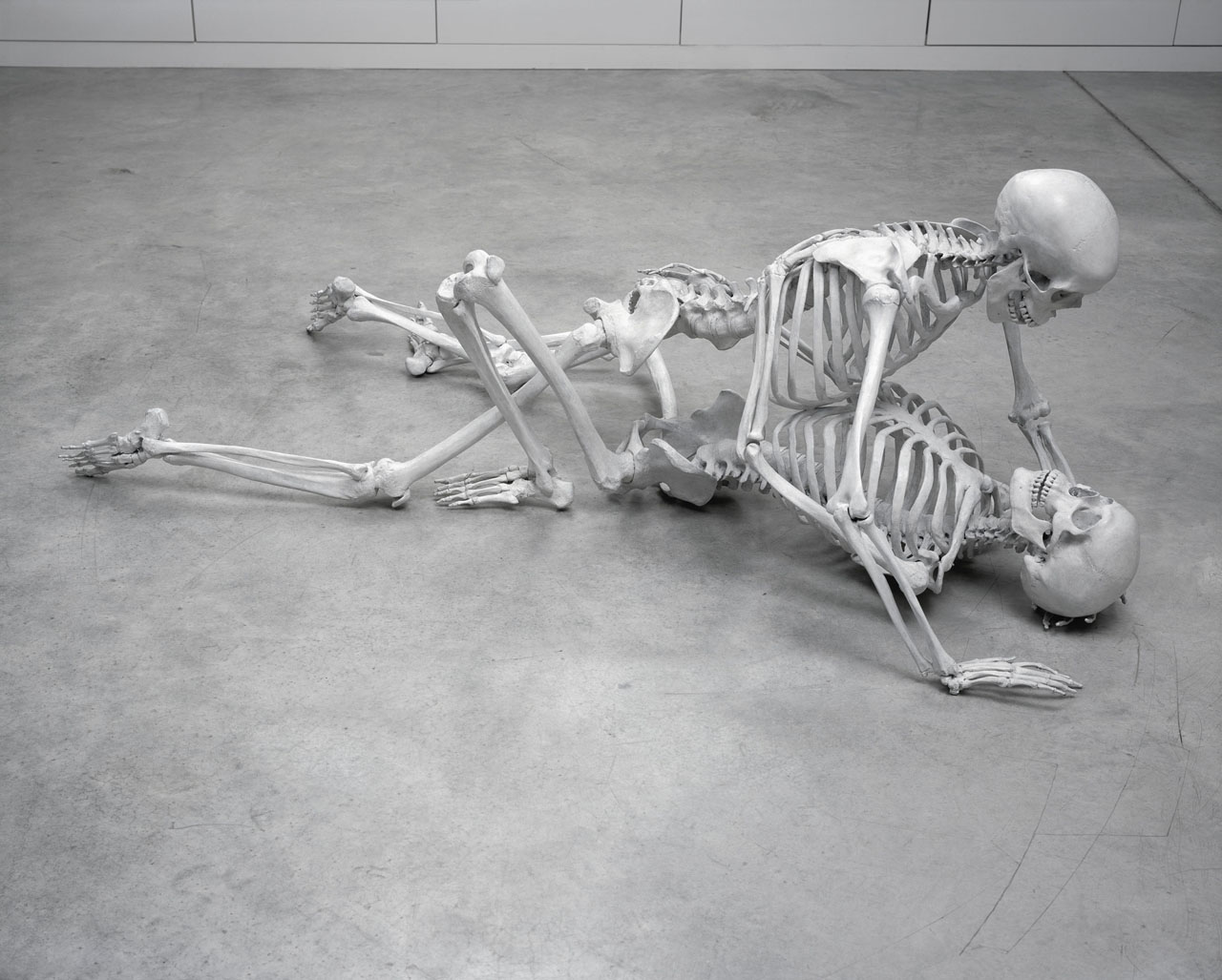

Gathering over forty recent works, DHC/ART’s inaugural exhibition by conceptual artist Marc Quinn is the largest ever mounted in North America and the artist’s first solo show in Canada

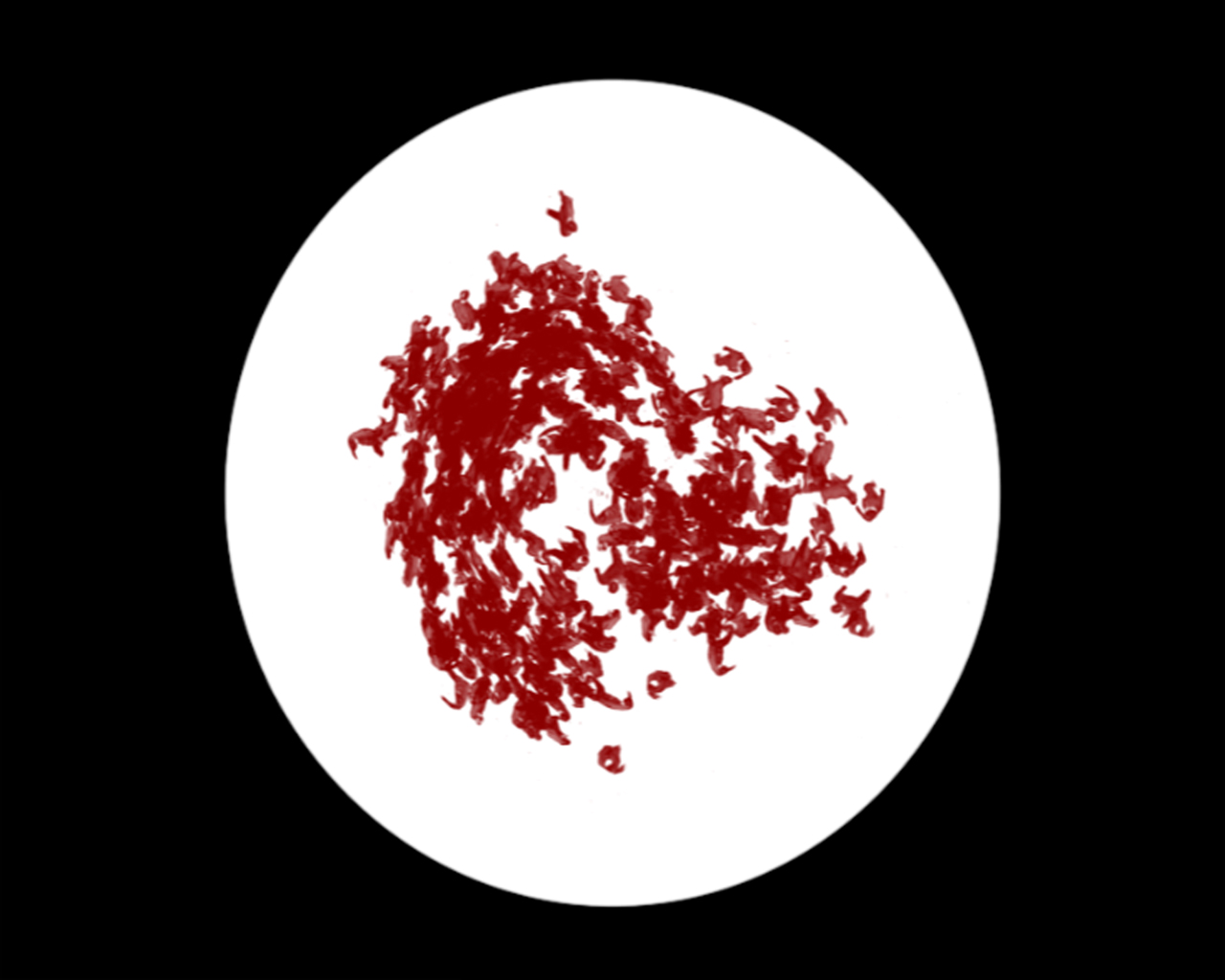

As shown through her diptych Alpenglow and Aurora, as well as through her 3D video animation Domestic Landscape, Quebec visual artist Sabrina Ratté likes to blur the lines between man-made geometric creations and wild natural landscapes. In this interview, she explains her interest in ambiguity, the in-between state open to interpretation, and the tension between the sublime and the unappealing. She also shares her inspiration with us, from architecture and painting to personal reverie.

PHI: Whether it be through Domestic Landscape or Alpenglow and Aurora, you seem to want to create an ambiguity between the architectural and the organic, between the immobile and the constant movement. Can you explain this choice?

Sabrina Ratté: I work a lot around this idea of creating ambiguous spaces, places that are not defined. They leave a lot of room for interpretation, for psychological projection. For example, Alpenglow and Aurora are both prints but they also utilize video projections, which creates an ambiguity about the medium: we are not sure whether we are seeing a video or a print image. I also like the idea of playing with the temporality of the video in relation to the fixed aspect of the print. There’s a parallel that can be drawn with an architect like Frank Lloyd Wright, who thought a lot about architecture in relation to its environment. I really like the idea that architecture is an extension of the environment, that it becomes an intrinsic part of it.

P: What impression are you trying to convey to the public?

SR: I create in order to materialize an abstract, and very strong, impression that can’t necessarily be transcribed into words. Images have this capacity of suggesting complex emotions. That's why I find it difficult to talk about my works, because I put a whole bunch of ideas, concepts and inspirations into them that then become crystallized in an image. Trying to explain it in words sometimes takes away from the interpretation one can have of it. What I hope is that the public can imagine themselves in the work and find some form of connection to their emotions, without there being anything didactic about it.

P: Just like it is pointless to dissect a poem…

SR: That's true, but a few years ago I asked author Darran Anderson (author of the book Imaginary Cities) to write about my work. He very kindly accepted. Reading someone else's written interpretation opened up new perspectives, it made me think in new ways. So in the end, maybe it’s all related to that approach of leaving a creation open to the potential for interpretation, and not locking it into one category.

P: With Domestic Landscape, you seem to want to highlight the origin of architecture, which is the human imagination. Conversely, have you ever also been inspired by certain architectures to build on your imagination?

SR: There are some inspirations that cut across all of my projects, but there are also specific inspirations for each project. Generally speaking, architecture evidently has a great influence on me. We talked earlier about Frank Lloyd Wright, and there are other very famous architects too, like Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe or Ricardo Bofill. When I moved to France, I made a video series during a residency called Machine for Living that was inspired by the new cities around Paris, with architecture from the 60s that’s completely psychedelic, very utopian: the Espaces Abraxas, the Grande Borne, the Aillaud Towers... For this project, I even took photographs of these places and integrated them into the video. I also drew a lot of inspiration from Éric Rohmer's films, including Boyfriends and girlfriends, which contains a whole commentary on new cities, at once atrocious and beautiful. There's something sublime, unappealing, and terrifying, but at the same time very interesting aesthetically. And so we come back to this idea of tension.

P: Like in a painting by Chirico. It's empty and nightmarish, but it almost feels good…

SR: I don't believe in utopia. I think we have to learn to live with this condition, to live with ambiguity, with contradiction, and to find a way to redefine our relationship to the present, to other beings. In my works, as in the works of Chirico or in places like new cities, we find this aspect to them that is seductive yet cold. And it's all about finding a way to navigate through that.

P: What the works in the Emergence & Convergence exhibition all have in common is that they form a symbiosis between nature and technology (or architecture in this case). Do you think that these two extremes will one day be able to coexist harmoniously in everyday life?

SR: I find it interesting that we consider technology and nature to be in opposition with each other. Right now, I'm reading Donna J. Haraway's book Staying with the Trouble. From what I understand, today, in this Anthropocene era where humans have completely transformed their natural habitat, which is the Earth, our impact on the environment is so great that it is impossible to separate nature from technology. All of the nature around us has been completely altered by humans. Ultimately, we are nature ourselves, we are part of it, so technology is also part of nature. For me, these two things are not necessarily extremes. There are more and more architects thinking about environmental issues, with green roofs, hanging gardens... So yes, one can imagine that we are moving towards a more environmentally conscious society, with a balance between nature and architecture. At least I hope so.

P: Do you foresee a future made entirely of organic architecture or of architectural nature (modified by humans)? In which direction do you think we’re going?

SR: Donna Haraway wrote that our technology has become so lightweight that it gets lost in the environment. You can't even tell anymore. I find that quite fascinating.

Foundation

Gathering over forty recent works, DHC/ART’s inaugural exhibition by conceptual artist Marc Quinn is the largest ever mounted in North America and the artist’s first solo show in Canada

Foundation

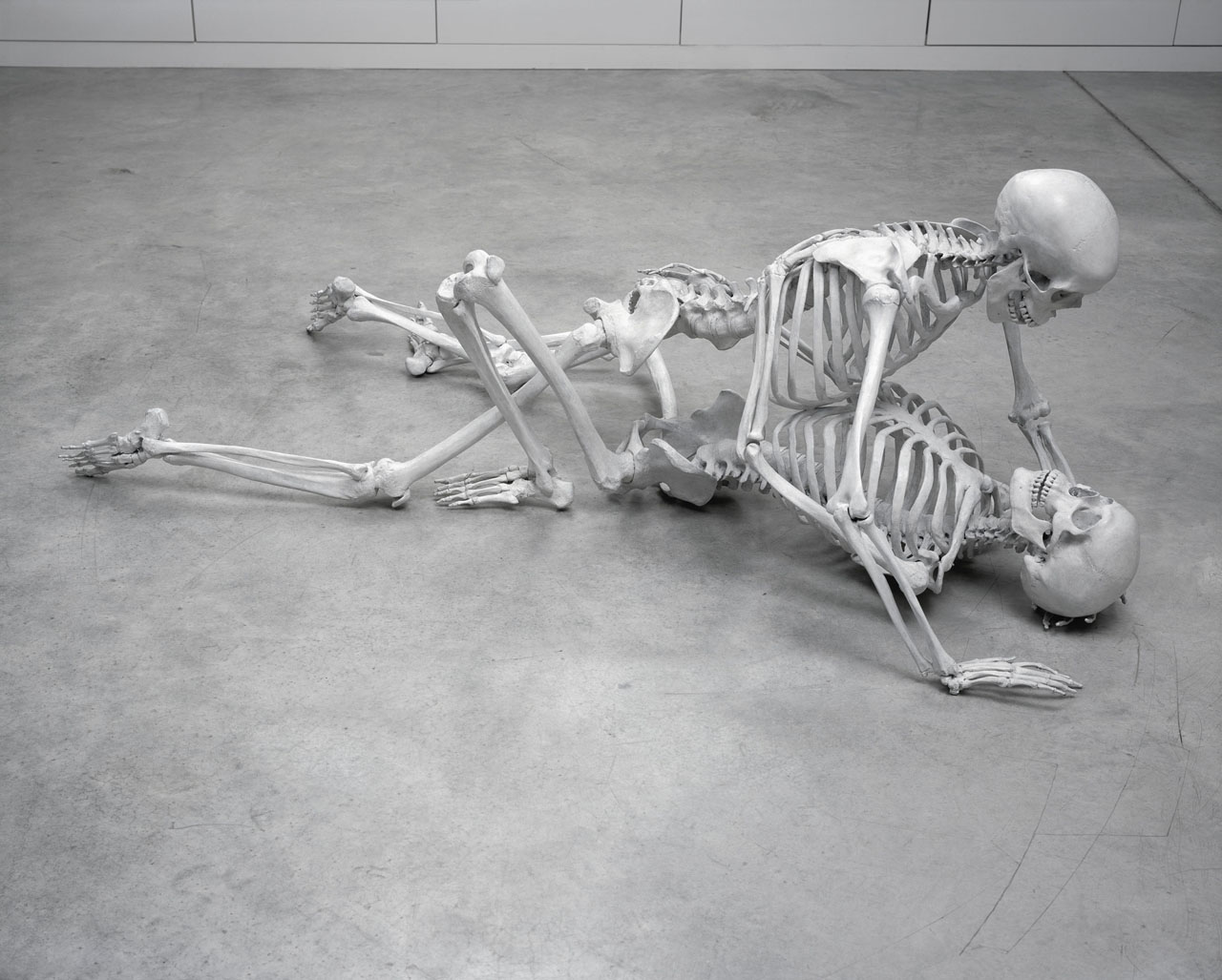

Six artists present works that in some way critically re-stage films, media spectacles, popular culture and, in one case, private moments of daily life

Foundation

This poetic and often touching project speaks to us all about our relation to the loved one

Foundation

DHC/ART Foundation for Contemporary Art is pleased to present the North American premiere of Christian Marclay’s Replay, a major exhibition gathering works in video by the internationally acclaimed artist

Foundation

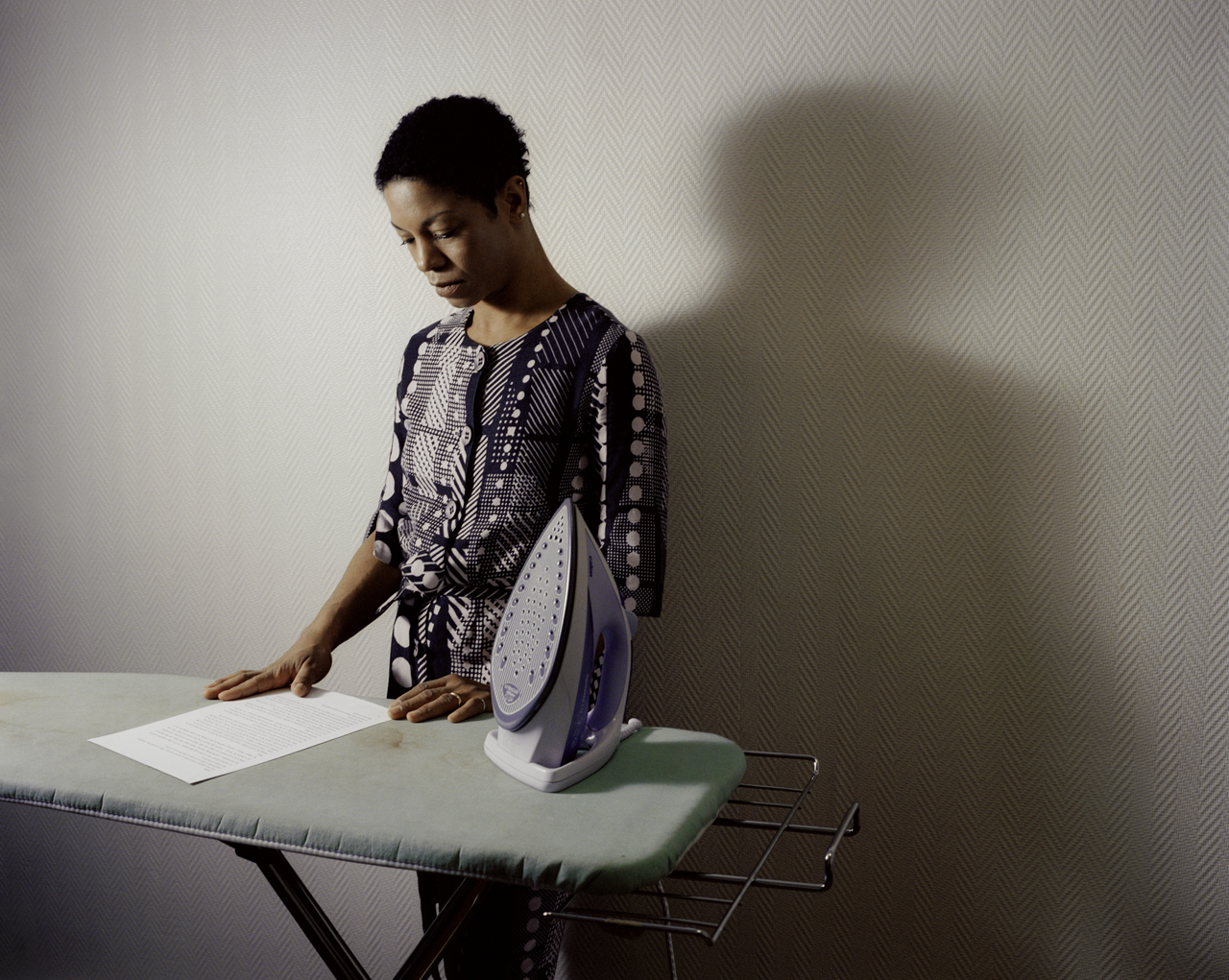

DHC/ART is pleased to present Particles of Reality, the first solo exhibition in Canada of the celebrated Israeli artist Michal Rovner, who divides her time between New York City and a farm in Israel

Foundation

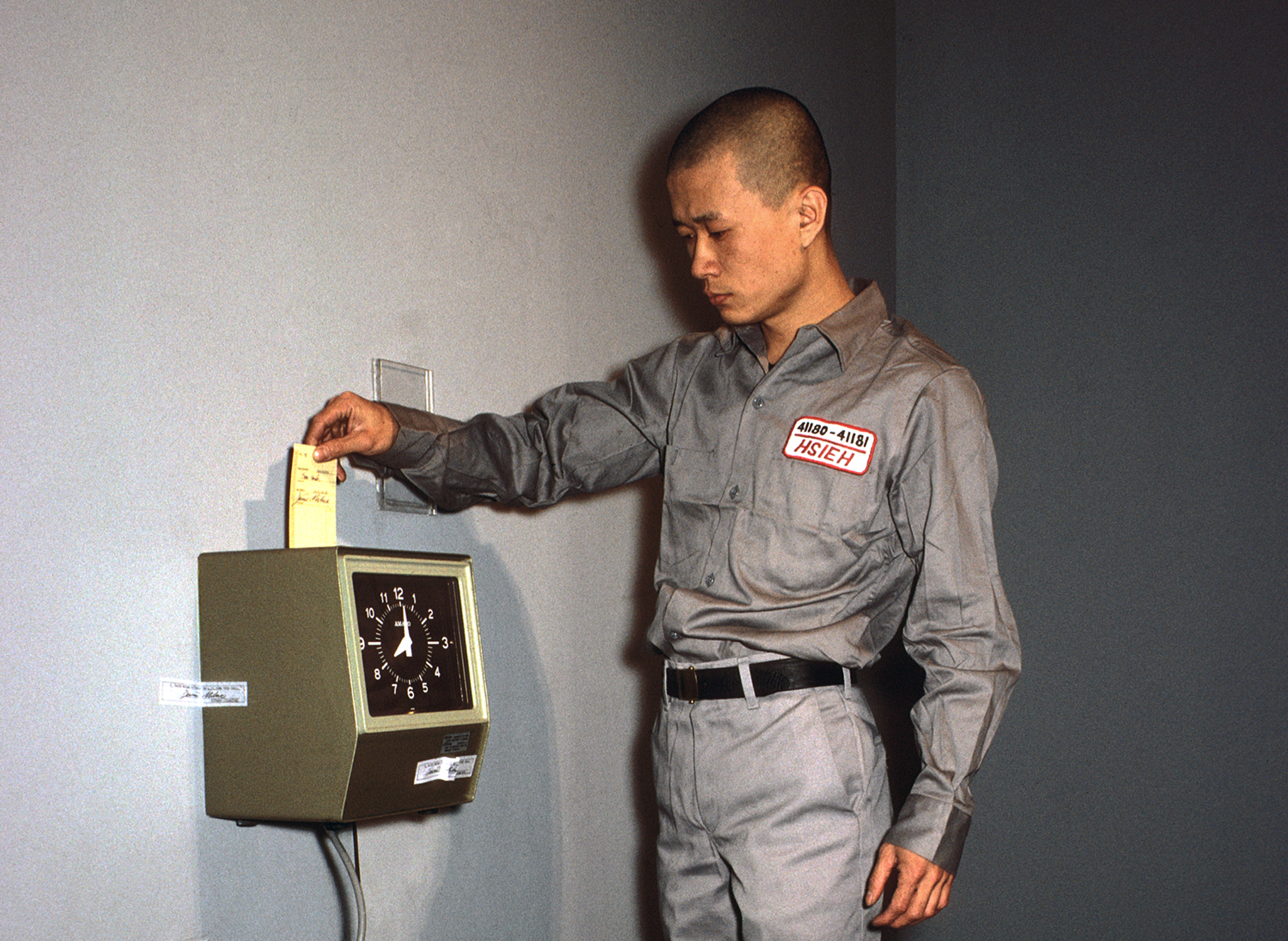

The inaugural DHC Session exhibition, Living Time, brings together selected documentation of renowned Taiwanese-American performance artist Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performances and the films of young Dutch artist, Guido van der Werve

Foundation

Eija-Liisa Ahtila’s film installations experiment with narrative storytelling, creating extraordinary tales out of ordinary human experiences

Foundation

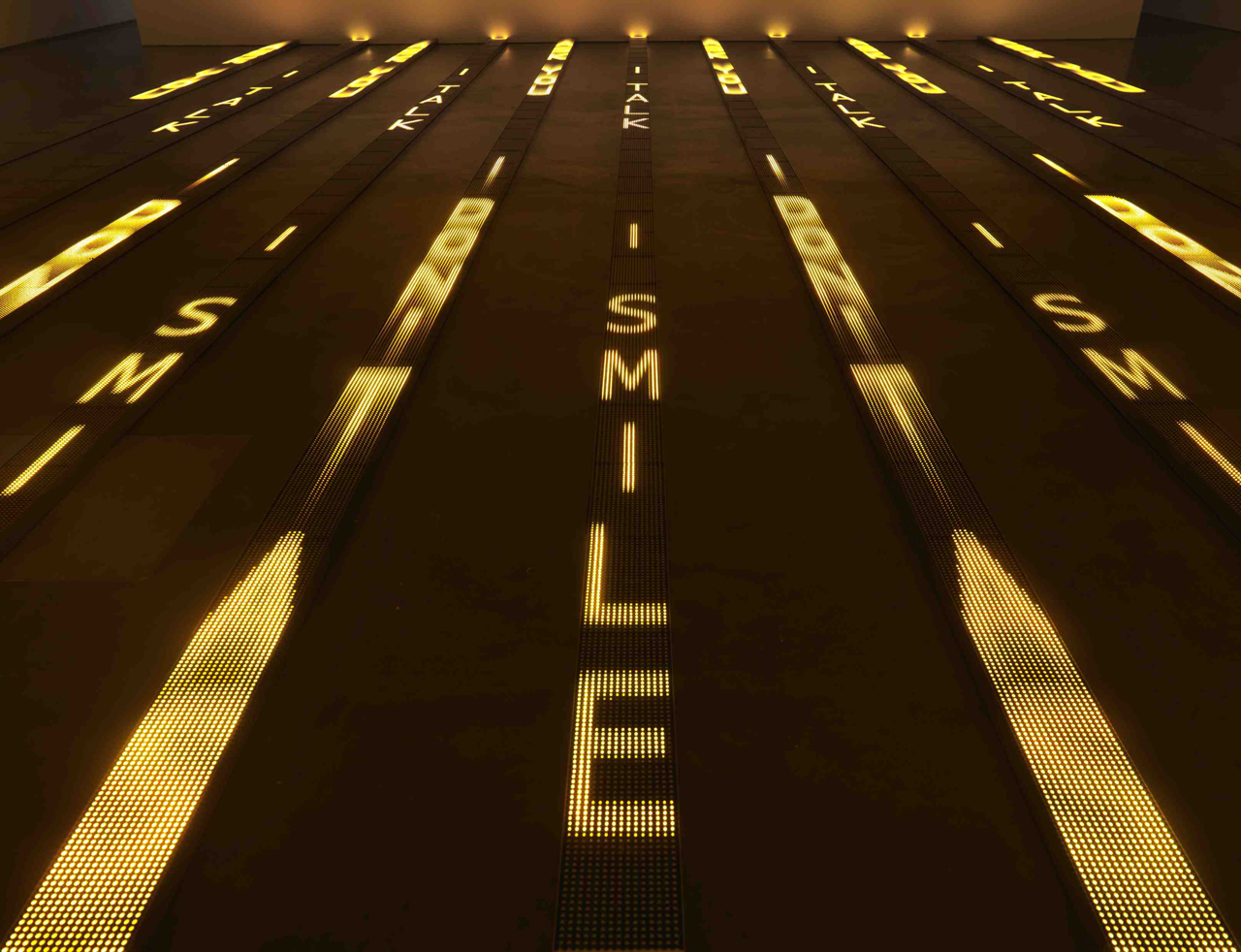

For more than thirty years, Jenny Holzer’s work has paired text and installation to examine personal and social realities