PHI IMMERSIVE

The PHI Immersive Residency is a 4-week program with PHI Studio focused on the development stage of a proposed project.

For the first iteration of the PHI Immersive Residency, PHI Studio was thrilled to welcome the selected laureates, creative duo Iolanda Di Bonaventura and Saverio Trapasso, to develop their project 0 over eight weeks.

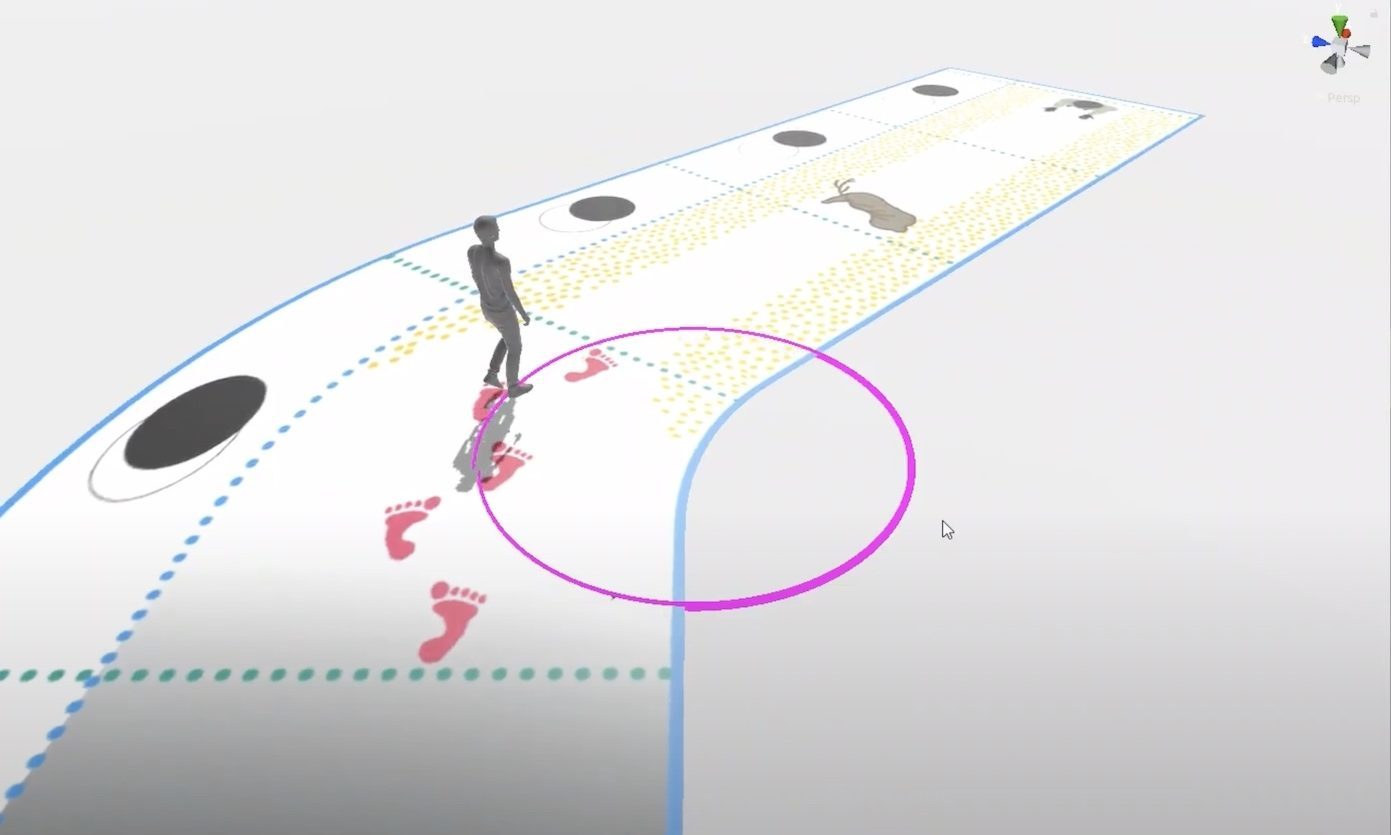

Iolanda Di Bonaventura and Saverio Trapasso are a pair that couldn’t be more different but also complement each other perfectly. Iolanda has a strong aesthetic vision informed by her awareness of herself and others, her practice in visual media, and her background in dance movement therapy. Saverio is a creative technologist who doesn’t recognize the artistry in his work that continually inspires him to push the boundaries of his abilities and communicate Iolanda’s vision. Their piece 0 was a virtual reality installation that would, through the barest of elements (an avatar of ourselves to mirror our motion, a vast and flowing field of wheat), reconnect us with our body, inspire us to feel how we move differently, and meditate on the cycle of birth and death.

My role during the residency was to help them develop the visitor’s journey before and after putting on the VR headset. In the final week of their residency, I found some time during their busy schedule to sit down and talk to them. The conversation came naturally, and I discovered two individuals with very unique, sensitive, and mindful approaches to new media and XR technology.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Andrew Gray: Can you start with a summary of your practice?

Iolanda Di Bonaventura: I would say that the fundamental part of my artistic practice is the investigation of the self. I have used so many tools for achieving that goal, though “achieving” is not the right word because the investigation of the self is not something that you can be given or that you can possess, it is a continual process. I started drawing, and then I decided to take pictures. The discovery of photography was an important part of my artistic process because it happened when I was quite young, a teenager, and I come from a city that has been destroyed by an earthquake. So while my friends started to take drugs, I just discovered photography and this is what saved me in some way. But I found myself thinking that it was not enough even though I have deeply studied the light and studied all the technical processes needed to achieve what I wanted to achieve. And so I moved on, and I moved to video, and I searched for myself in video too, then animation, then performance. We could say that what brought me towards this discovery was the feeling of being completely uncomfortable in my body, but it is not the typical sense that we see among teenagers and women who say they don’t feel comfortable in their bodies. This is not the feeling I have, the feeling I have is more related to why am I here? Why do I have a body? Why is it so uncomfortable for me to exist? My art helps me to explore, I wouldn’t say “the answer” because there is no answer, but maybe to discover the question. I read somewhere that professionals don’t have the right answer but just have the right questions. So let’s say that for me art is the research of my own question.

Andrew: So your practice involves questioning how you feel connected or disconnected to your own body?

Iolanda: Exactly. Then I met Saverio, and I was very interested in the more technological side of creation and avenues offered by new media. We had the idea of establishing a collaboration between us. 0 marks the third project that we are working on together.

Andrew: Anything you would like to add, Saverio?

Saverio Trapasso: *laughs* I’m not sure what I can add, I mean, she’s the artist. I’m just a tool, a human tool.

Andrew: I’d like to take a moment to unpack the word “immersive” together. As the name of the residency, immersive encapsulates many forms of new media storytelling, and it still remains a relatively new concept that I see applied to a whole host of different things. I feel like it has become so ubiquitous that it is sometimes hard to define. How would you define “immersive art”?

Iolanda: I don’t recognize myself as an artist, or an immersive artist, or somebody who deals with an immersive installation. I don’t feel this connection between me and this word. “Immersive art” doesn’t mean anything, and from what I saw, it is more related to entertainment. Art’s main purpose for me is to create a connection between human beings, to create communication, and to create a space in which this communication can happen.

[...]

Saverio: It’s really confusing. I have my own idea of what immersive perception means. But talking about immersive perception is different from talking about an immersive experience because the word experience means many different things in many different scenarios. So it’s unfair to talk about this topic you know. *laughs*

Andrew: Would you say that there is an immersive aesthetic?

Saverio: Since my background is in the world of technology and video game production, I’d like to clarify the fact that the word "aesthetic" has a different, perhaps deeper, meaning for me than someone who roots their experience in, for instance, the world of cinema or art. When we talk about "aesthetics," in the world of video game experiences, we are not only referring to the visual or sound style of a project, how explicit or implicit it is, how much it communicates to the viewer, and in what ways it communicates to the viewer. In the "aesthetics" of video games, VR, and immersive experiences, the word also includes how usability and interactivity are integrated within the experience stream, and how this is communicated to the participant.

Iolanda: I’m not sure I’m the best-qualified person to answer the question, "does an immersive aesthetic exist"?

In this residency, we’re not only putting ourselves out there as creatives, but we’re also learning about the substantial differences that exist in the perception of the art world in Italy —our home country—and Canada. I think it’s easy to imagine how "Italian art" is anchored in the past, taking away space from research and innovation; a perspective that is completely reversed here in Canada.

Andrew: Do you believe that the audience for new media is moving past this stage of fascination with technology, and they’re starting to arrive at a more complex appreciation of the wide range of possibilities of experiences that can be created using the techniques and technologies available?

Iolanda: I think that as artists, as the community that works with this new media, we have a great responsibility in shaping the way the audience perceives, opening doors inside their brains to show them other ways of using technology. Though, from my experience, artistic needs often conflict with marketing and the rules that dominate the selling and distribution of an art piece.

Andrew: What is your feeling about new media in a market-driven atmosphere? Do you feel that it compromises your vision artistically knowing that you need to produce something consumable?

Iolanda: I feel the constraints of the conditions in which we are living. And I don’t think that we’ve had the chance to meet our audience. We haven’t really had the opportunity to show something for us to arrive at a point where we question ourselves, “How do I feel producing something, which is consumable?” The question I’d like to ask is “Are the questions that I’d like my audience to wonder… are they consumable?” Are the seeds that we would like to put inside the spectator consumable? I hope not.

Andrew: When we talk about cinema, we often borrow language from photography and theatre. Do you feel like immersive art and new media, especially XR artworks, take a lot of the knowledge and language from the video game industry?

Iolanda: I think there is a big prejudice against the word “video game.” And I’m not a video game lover at all. But looking at it from the other side, as someone who deals with the production of something that has so much in common with the video game world, I’m deeply aware of the knowledge that is behind this process. I studied cinema. I have a degree in cinematography. And I know the process of creating something in the cinema industry and I know how much effort it takes, but it’s nothing compared to the work that goes into the production of a video game product. Nothing. I think that we have to be grateful that this knowledge exists. It is a valuable tool for us if we can only learn to just see beyond “the score,” what's “the goal,” or “the number of headshots.”

Saverio: This is a difficult subject because I come from the world of video games. There are a lot of misconceptions about the world of video games. I think the word "video game" creates a lot of preconceptions and a lack of confidence, especially in the generations that came before us. That it's an empty form of entertainment.

[...]

No one talks about the psychology of gamers. I think the studies done on the psychology of video gamers, can teach us a lot about our identity and what drives us as human beings. [...] There are people who through virtual and immersive experiences (whether video games, virtual worlds, etc.) satisfy their need to socialize, and others who are attracted to interacting with the environments.

I believe the drives and needs are elements that define us not only as gamers but also as human beings. I feel that the world of video games can teach us a lot about who we are.

To say that gaming helps us reach a certain level and degree of satisfaction—subjective and dependent on our psychology—is a bit of a metaphor for life. We call this activity "gaming," often forgetting that it is… actually an activity and that this activity contains a base of knowledge that can be used to shape a new language. A base of knowledge that doesn’t come from a video game culture but comes from human examination, from human behaviour analysis.

Since it’s a young discipline, it’s a young subject, I believe we need this to become a discipline taught in schools. Returning to the topic of the responsibility of the creators, a better understanding would help us to contain the negative aspects of the video game world, such as addiction. For example, if we gave six to ten-year-olds the tools to learn what an addictive game is, and to recognize what makes a product addictive, it gives them the power to choose. I think that now, we’re lacking this power because we’re lacking knowledge.

Iolanda: I just want to add a small thought. What a game and an experience have in common is their shared goal of fulfilling a need in the visitor to be entertained. I hate the idea that I’m in this world to be entertained. Entertained, from what? This kind of need, which for me is quite new in the way it manifests itself, is to capture people’s attention, as a diversion from everyday life, and convert this attention into entertainment. I think it’s so cruel, and the audience manifests this kind of dependency from that. It’s a matter of power, and addiction is a matter of power as Saverio said. It returns to what we said at the very beginning. The artist needs to recognize the importance of their role in shaping the imagination of the audience. Shaping the imagination of the audience means that the audience reconsiders the role of entertainment in their life.

Andrew: If I understand you correctly, the role that you would like for the artist to play, is to provide an antidote, or an alternative, to this compulsion in society to seek entertainment. I think this also plays back into your problem with being an artist in an art market because marketability gravitates towards this compulsion to seek entertainment. How would you reconcile this, even as someone critical of the art market, and this need to present your work as a product, that doesn’t mean that you can’t present a piece that is appealing to someone who recognizes their dependence on entertainment? How would you appeal to someone who is oversaturated with entertainment?

Iolanda: We don’t have the answer for that, and we are struggling to find the answer to that. How can we make people aware of this need to unplug, to free themselves from the compulsion of needing to be entertained? I don’t have the answer, what I will say is just something I realized in the last few days about the piece we have created. I thought about all the time that I have spent trying to explain the narrative, which is very, very simple, so simple that it can be confusing to others. “Is it really that simple?” is the feedback that we have received from so many people, and I’ve understood it as a compliment. Yes, it is that simple. The narrative of the experience is not something that happens outside of you, the narrative of the piece is based on what you feel within. Maybe the audience that comes with the expectation that they are going to have a lot of action inside the VR experience will be very disappointed, it will take a lot of training for them to understand its concept. But if even a low percentage of them can tell us that it was good, that will mean that we have reached our aim. I mean with our testers, it was beautiful to look at them, it was beautiful to see the shape of the narrative that was taking place inside them. Instead of outside.

Andrew: Rather than tell a story, or communicate a narrative, I feel like your work is about establishing the conditions that frame the spectator, and then within it, they can live their own story.

I think this is an important aspect of your work, using the technology not as a storytelling device, but as a tool to create conditions or relations–a space or environment to let the spectator discover themselves.

Andrew: You aim to provoke a transformation in your viewer with an experience that asks them to acknowledge themselves, but some people create barriers and mechanisms for coping and look to entertainment for an escape from reality. How, as an artist, do you approach your responsibility towards those who might be disarmed, or triggered, by an experience?

Iolanda: I have an answer, which is very articulated. I approach this question not as an artist, but as a therapist, specifically a dance movement therapist. I would say that you only see the most difficult parts of your life, and you only recognize your trauma when you’re ready to see them. If there are too many coping mechanisms creating a barrier between the audience and the piece, they will simply refuse to recognize the sense of it. They won’t live any kind of awakening, nothing. They will just get bored. So maybe the question we should ask is, “how do we take care of the people who have a strong physical reaction?” not “how do we take care of those who need to look deeper into themselves, who use technology as a coping mechanism,” because I am not sure this piece will bring them there.

Andrew: Maybe we can talk briefly about embodied experience. The experience you have created is meant to reconnect the spectator with their bodies. Do you think it's counterproductive to offer this kind of presence through virtual conditions? What do you believe to be the limitations of trying to provoke a deeper connection to the physical world, to remind us of our bodies, through virtual experiences?

Iolanda: I think that the most dangerous part will be the shift in meaning. Virtuality to reality. But I think that if we set clear and protective boundaries, technology can help us facilitate this connection for us. So yes, I think this is my answer.

Andrew: How would you react if a spectator came and did the piece. And their reaction was, “well, why wouldn't I just go to a field of grass? Wouldn't that be more immersive or wouldn't that be more real?”

Iolanda: I actually feel that that would be the best reaction.

Andrew: You speak of your experience as a movement therapist, and I know you have quite a sensitive connection in your practice between the mind and body, and the psychological and physical aspects of experience. How does this inform your approach? Or how do you integrate these kinds of concepts into your practice?

Iolanda: For me, this piece is completely based on the principles of the disciplines that I studied. Let’s take a step back, a dance movement therapy session is something that happens between two people, or a person and a group of patients. We have a therapist, and we have patients. The therapist knows from the patient's body language what is blocking them. For them, it’s important to learn about themselves and to propose an activity using their voice. It is important to let the patient discover something in their way by performing those moments on their own. This is the practice. But the decision when creating this piece was not to adopt this kind of straightforward approach, but instead to create a design that could facilitate this reconnection with their movement. I mean, turning around inside the wheat field is quite instinctive, and I saw a lot of people doing that without telling them that this was the behaviour I want to provoke in them.

For me, a person must perceive the three-dimensionality of space. Having the opportunity to explore a new dimension activates different parts of the brain, which activates different memories, activating different patterns. If there are not too many coping mechanisms, creating a barrier between the person and the experience, that is the moment that something happens. And you can discover that it is very beautiful to dance with yourself, or you discover that it is a terrible experience to dance with yourself because you see yourself only in your vulnerable personality instead of the beautiful person that you are. So you project something on the avatar. It’s interesting.

Andrew: As someone who has started in photography, and has experimented and video, and installation, dance, immersive experiences, or interactive installations, how do you believe your vision translates from one to the other? Do you believe that between each medium, you have a different language of expression?

Iolanda: My answer will be that I feel that there’s a connection between all the work that I have done. This is an intimate connection, but it is something that is also a reflection of the individual who watches the piece. I would say that for me, artists cannot wear a mask. When you create something the audience deserves an artist who doesn’t wear a mask. And so, the exercise central to my practice is “how do I put my mask away?” And if I can put my mask away, I can be sincere and I feel I can be recognized.

Andrew: I find this is an interesting point but leads me to ask the question. Many of your pieces are self-portraits, and in most of these, you hide your face. Your face is often covered by your hair, masked by an effect, or your body is positioned so that we are unable to see your face. Why are you apprehensive about including your face in your work?

Iolanda: I don’t want to interpret it that way. Let’s say that my way of putting the mask away is to free myself from the fact that I am my face.

Andrew: You mean to say that there is too much importance or signification in your face, that the features of your face are themselves a mask?

Iolanda: Too much maybe… or maybe not so much, I think for me it is not so much. My practice is, yes, standing in front of a camera when it’s a self-portrait, but my practice (and I love the fact that you describe art, not as a job, but as a practice) is what happens before we take the picture or before we take the video. I spend so much time finding the right environment, with the right light, with the right story with the right mood. And then to position myself within that environment, "who am I now?" I mostly discover that I am nobody, and I feel the power of being nobody. Somebody that doesn’t have a face doesn’t have to have a face, doesn’t have to have a right position, doesn’t have to have proper body language, and doesn’t have to feel comfortable in doing something that he or she hates. I’m so uncomfortable when people take a picture of me. And I am sincere, this is what I offer, I offer the fact that I am not comfortable in this world. And by doing this, I think people can find a kind of relief knowing that maybe they’re not alone in this feeling. I don’t know, maybe.

Andrew: Talk to me more about this concept of foreignness or strangeness or the unrecognizable or the undefinable, they seem to be a recurring theme, how do they relate to your images?

Iolanda: The most difficult part is to describe what can’t be communicated by using words. Something I have realized during this residency is that this space of indefinition cannot be reached with words. So I find myself unable to answer your question, to speak about it more. I just know that this dimension relies on my private self. And it’s not about “I don’t want to disclose myself” it’s just that I can’t do that, words are not able to reach that private space.

Spending time with Iolanda and Saverio made me question my ideas about immersive experiences. Maybe we need to rethink our relationship with stories. Maybe immersion is about immersing the individual in their own story, not at all virtually, but using simulated virtual reality to remind them that they're already living a story. They have their own body and experience, and the "immersive" aspect isn't an escape but an act of self-discovery.

The PHI Immersive Residency is a 4-week program with PHI Studio focused on the development stage of a proposed project.

Foundation

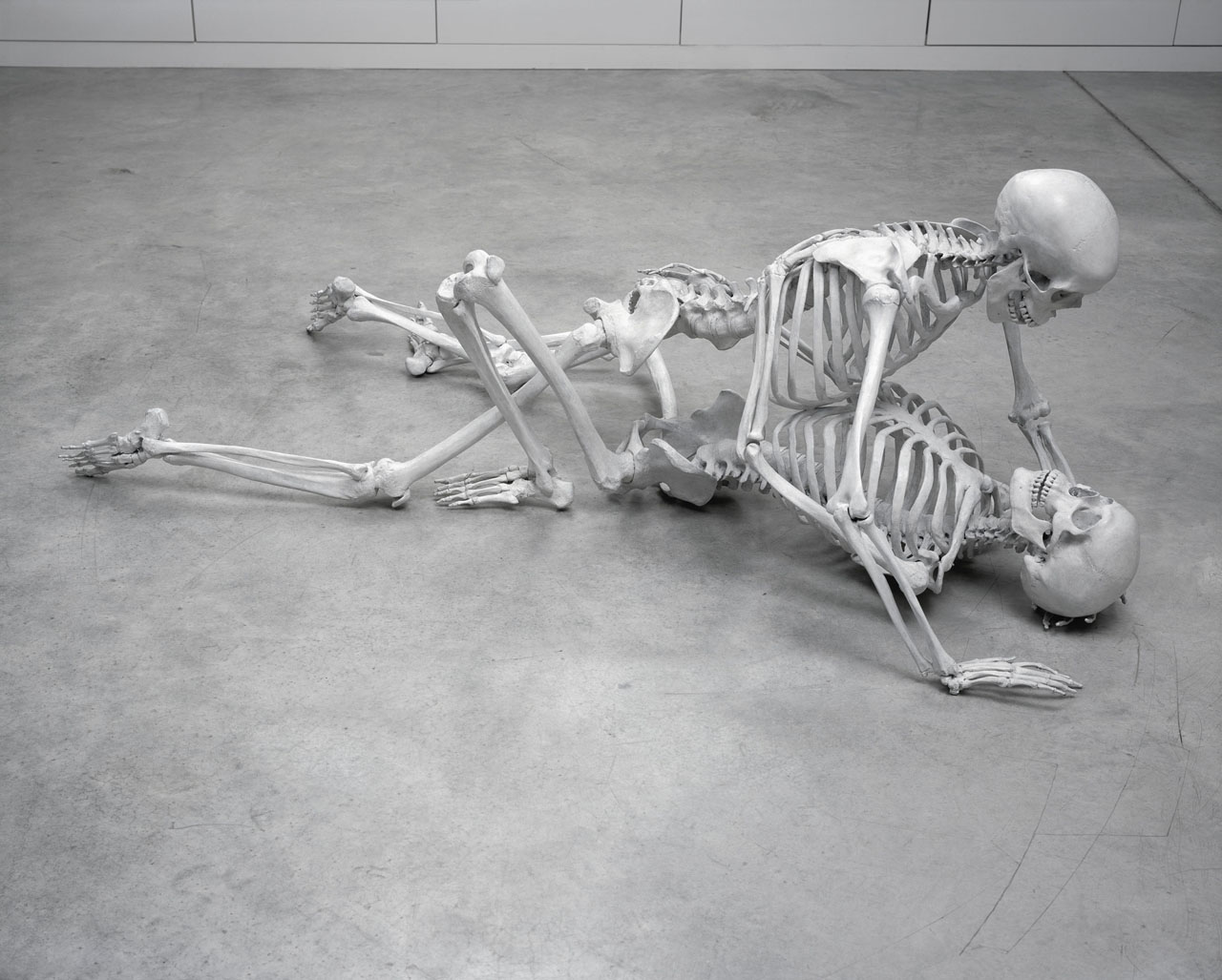

Gathering over forty recent works, DHC/ART’s inaugural exhibition by conceptual artist Marc Quinn is the largest ever mounted in North America and the artist’s first solo show in Canada

Foundation

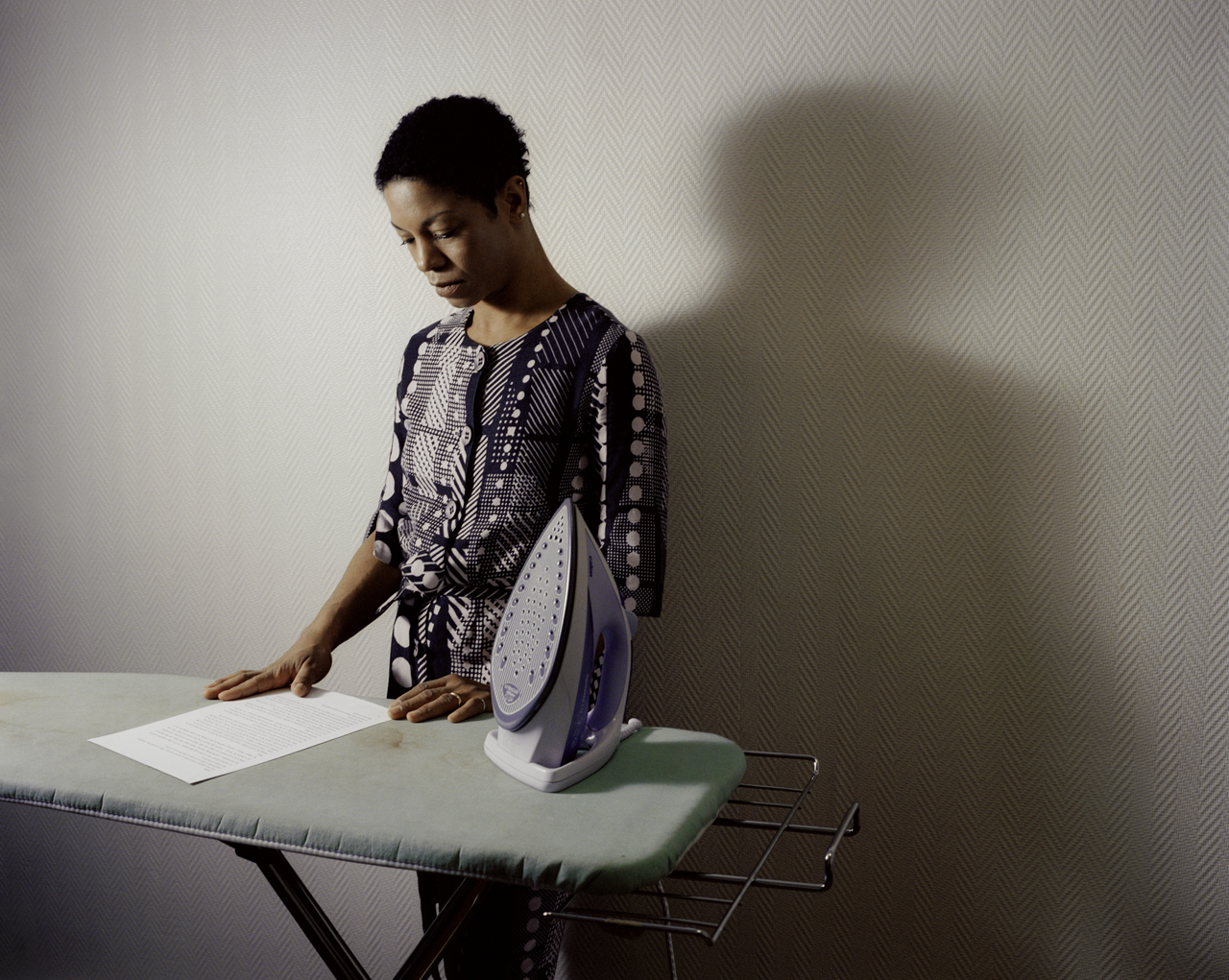

Six artists present works that in some way critically re-stage films, media spectacles, popular culture and, in one case, private moments of daily life

Foundation

This poetic and often touching project speaks to us all about our relation to the loved one

Foundation

DHC/ART Foundation for Contemporary Art is pleased to present the North American premiere of Christian Marclay’s Replay, a major exhibition gathering works in video by the internationally acclaimed artist

Foundation

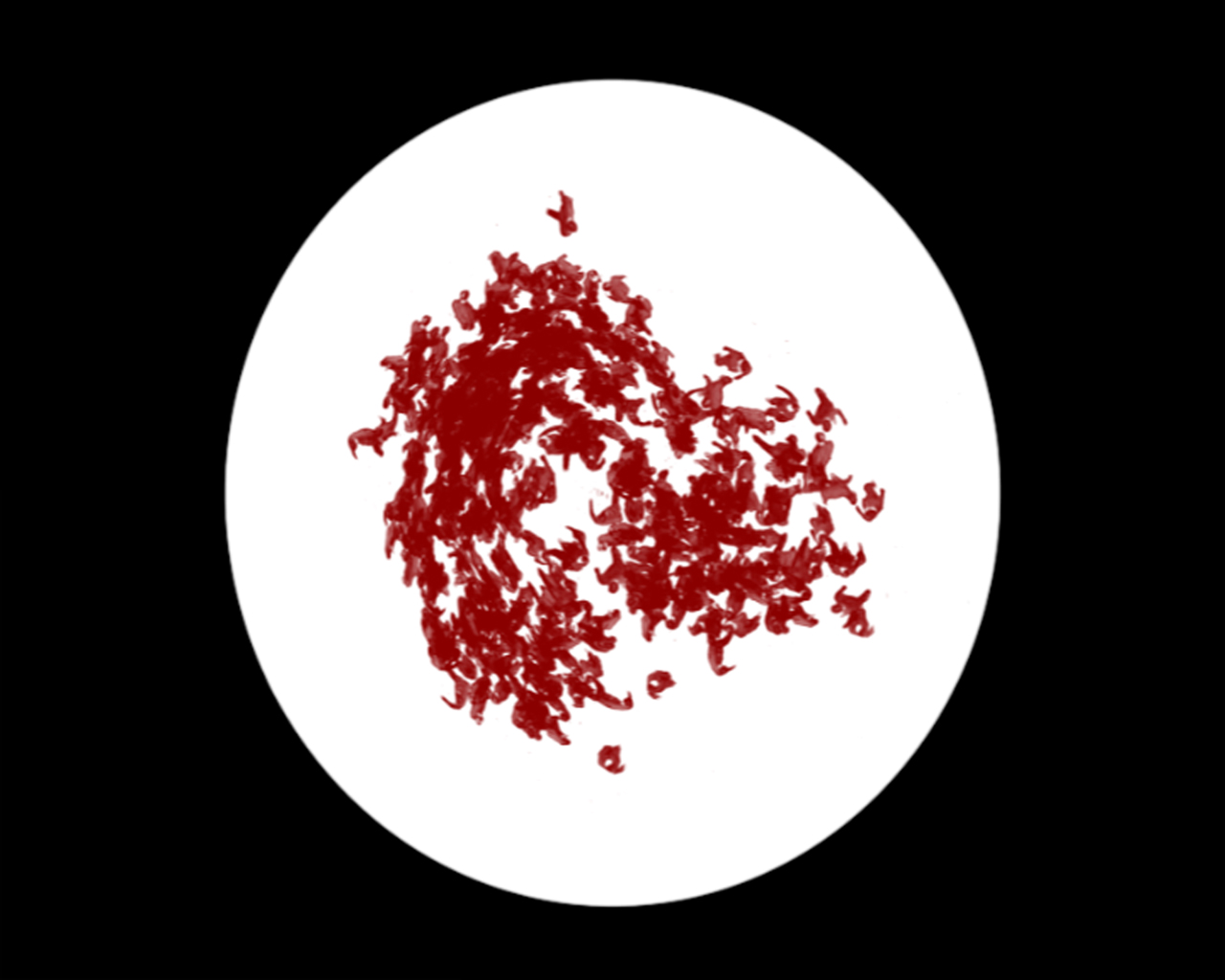

DHC/ART is pleased to present Particles of Reality, the first solo exhibition in Canada of the celebrated Israeli artist Michal Rovner, who divides her time between New York City and a farm in Israel

Foundation

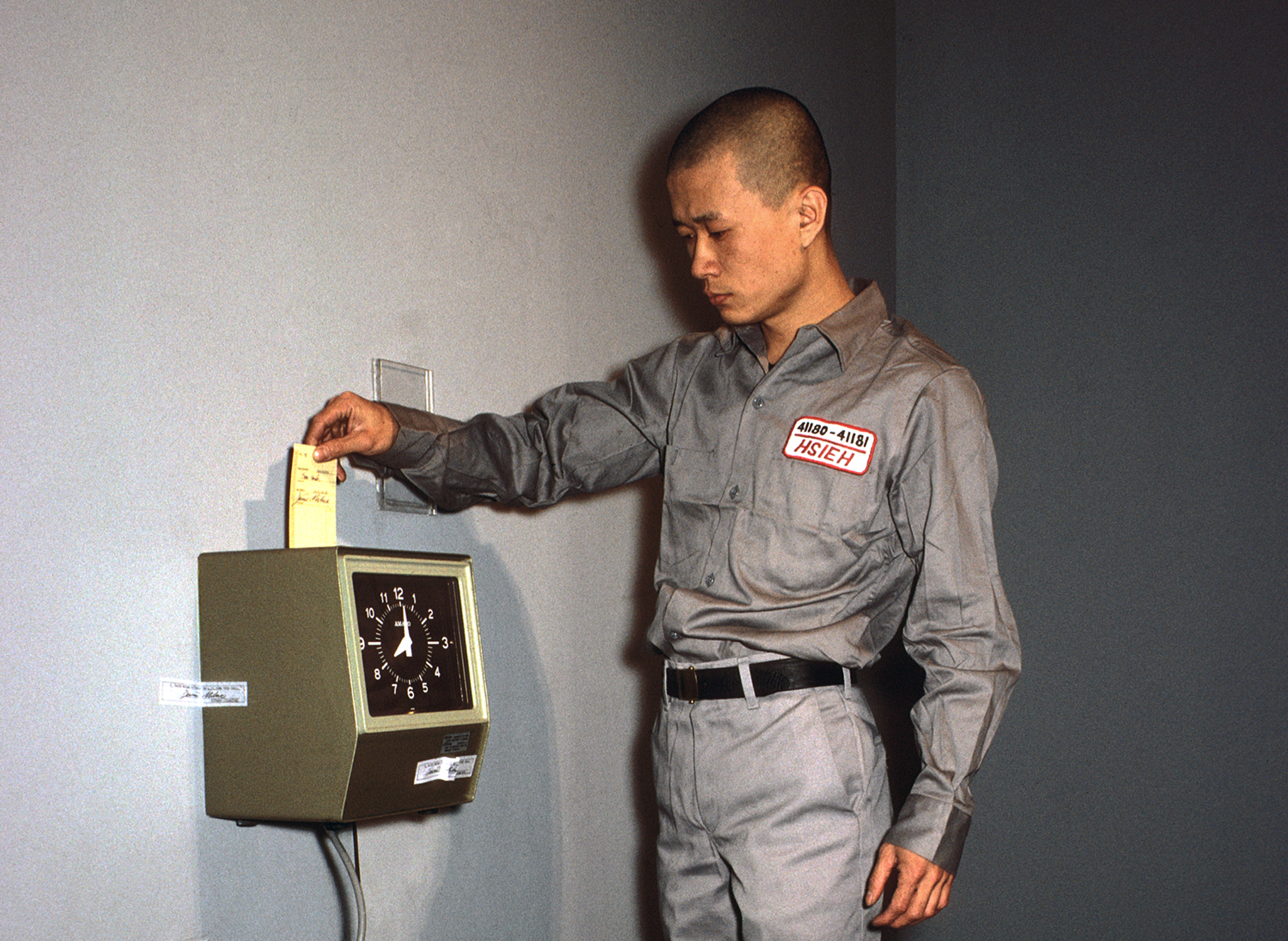

The inaugural DHC Session exhibition, Living Time, brings together selected documentation of renowned Taiwanese-American performance artist Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performances and the films of young Dutch artist, Guido van der Werve

Foundation

Eija-Liisa Ahtila’s film installations experiment with narrative storytelling, creating extraordinary tales out of ordinary human experiences

Foundation

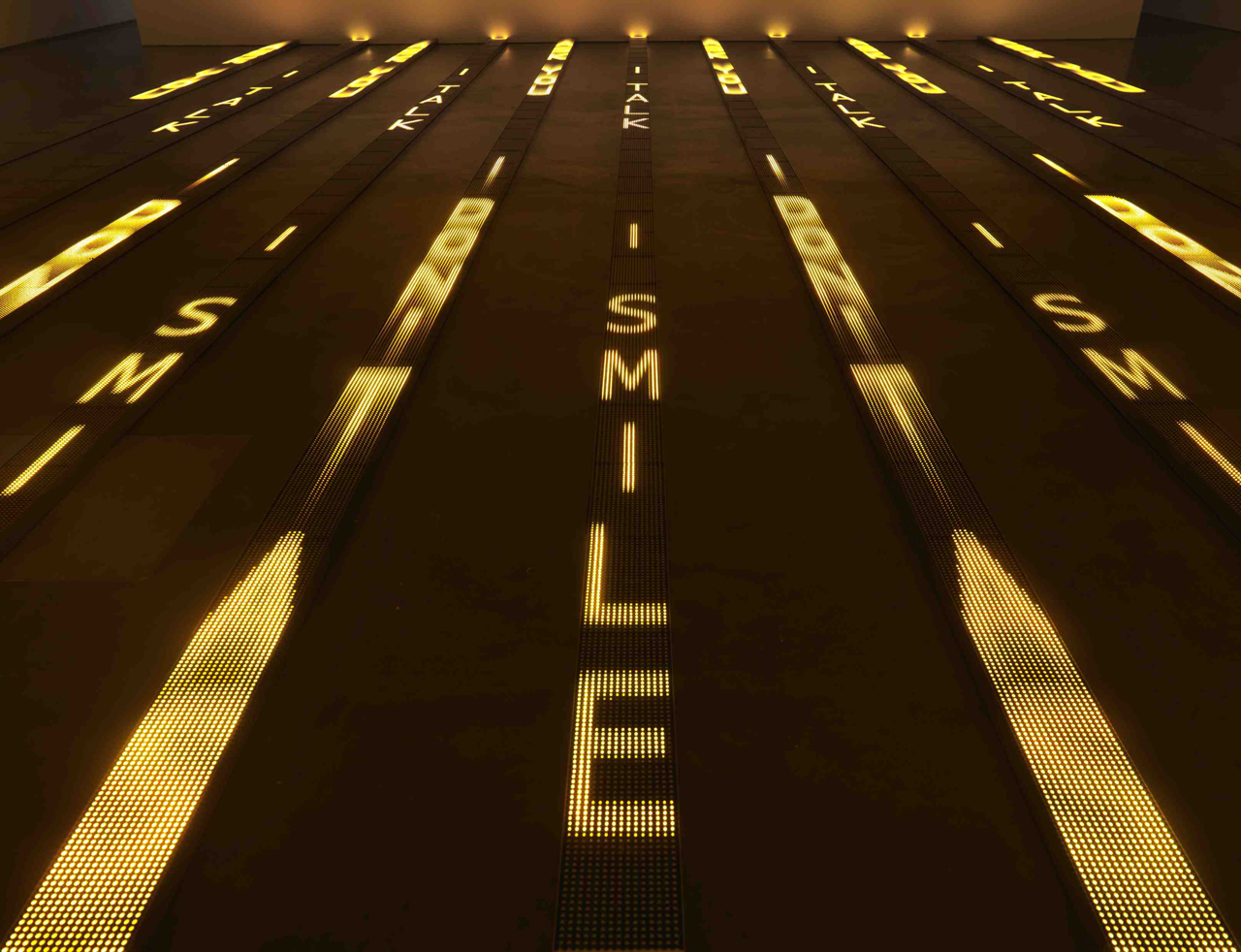

For more than thirty years, Jenny Holzer’s work has paired text and installation to examine personal and social realities