Foundation

Marc Quinn

October 5 → January 6, 2008

Gathering over forty recent works, DHC/ART’s inaugural exhibition by conceptual artist Marc Quinn is the largest ever mounted in North America and the artist’s first solo show in Canada

I just moved to Guelph this August, and being close by, I had the pleasure of interviewing Rajni Perera in her studio in Toronto. We spoke about her practice, the direction she’s taking in these critical times, our shared interests and the work presented in the exhibition RELATIONS: Diaspora and Painting at the PHI Foundation for Contemporary Art in Montreal.

Rihab Essayh: Hi Rajni, how are you?

Rajni Perera: Hi! I am good!

RE: For context, the first time I saw your work was last year during Art Toronto (2019). I got to see your exhibit Traveller at Patel Brown (or Patel Division at the time) and got to read some texts that Negarra Kudumu wrote about you.

RP: What! Were you there at the Traveller talk with Negarra?

RE: Yeah!

RP: Did you get to meet Negarra?

RE: Yes!

RP: OH! She is the one.

RE: Yeah she was eloquent and magnificent...

RP: She’s also stunning and her energy is wonderful!

RE: But I really appreciate that, and I appreciated how she translated your work and connected it with mythologies I didn’t know about.

RP: She’s a scholar; she has the keys to the breadth of information that as a maker I won’t necessarily have. A lot of times when I make my work, I act like I’m a conduit, and stuff just moves through. Negarra would see something and be like: “Excuse me, do you know about this and this and that?”. That’s the most wonderful part: to be able to interact with a scholar like her. She is very open, not academically elitist. She believes everyone deserves information, to partake in the great tradition of mystical work, and then she will frame it in a certain way that is so accessible.

RE: I totally agree. I got to learn about your past work through her texts in a very genuine and lovely way – like having this trace of all these past versions of you on paper.

RP: Yeah, it’s very strange and wonderful.

RE: Among the works I got to learn about through her texts and research, there’s Afrika Galaktika, a series that you recently took down from your website following the latest Black Lives Matter protests. Could you talk a bit more about the series?

RP: When I made that series, I felt like it was doing the right thing, and the series did do very well. It was really for Curtis [Talwst Santiago] to say during the panel: “Yo, when you were doing that, no one was doing that and I hope you know that Rajni!” But the political landscape really changes, and you flow with that and accommodate what is needed to go forward. In a lot of cases it means stepping back from a conversation that you don’t belong in anymore. I curate exhibitions sometimes; for that work, I should’ve sourced and facilitated from Black artists, and I didn’t.

Yes, I made them, and they are still doing some good in the world, but they are now removed from my website and my social media, even if the images are still on the Internet and all over the place. So I wanted them to exist because there are still a lot of people wanting to see them, and they are still helping folks that relate to it, but I don’t want it to be an infringement of another person’s culture. It seems like the most impossible task but hopefully it goes to a place where it’s detached from me but still doing some good.

RE: I don’t know if it will ever be detached from you. You stated that this acknowledgment is now part of the baggage of the work. I think it’s good.

RP: Aw thanks – that work is like 5 years of my life.

RE: I really respect your decision to take this work off your website. To me, it was the first time seeing this acknowledgment that Black, POC and Indigenous artists are often being regrouped as one multicultural group. Due to us being kinda mashed up together, it’s almost as if it allows us to get away with cultural appropriation. Cultural appropriation is not just a thing done by white folks. To me, this was wonderful to witness and it reinforces a more respectable positive change and support between marginalized communities. (...) It has its space and its importance. This makes me think of a quote that I love, do you know FKA Twigs?

RP: FKA Twigs? I really like her visuals, and she works with Andrew Thomas Huang, who is one of my favourites.

RE: I know, I’m still a bit angry that I didn’t get to meet him!

RP: Why, how?

RE: I was supposed to present an art installation for the AGO MASSIVart party last spring, and he was part of the artists presented. And it got canceled because of the pandemic.

RP: I wanna cry!

RE: I legit cried the day they cancelled the event… anyway.

RP: Aw...

RE: So in FKA Twigs’ home with you she says: I've never seen a hero like me in a sci-fi. As a Moroccan woman who grew up in the Western world loving sci-fi films, this quote really resonated with me and sort of echoes a void that your work fills.

RP: Oh wow, I need to listen to that song now!

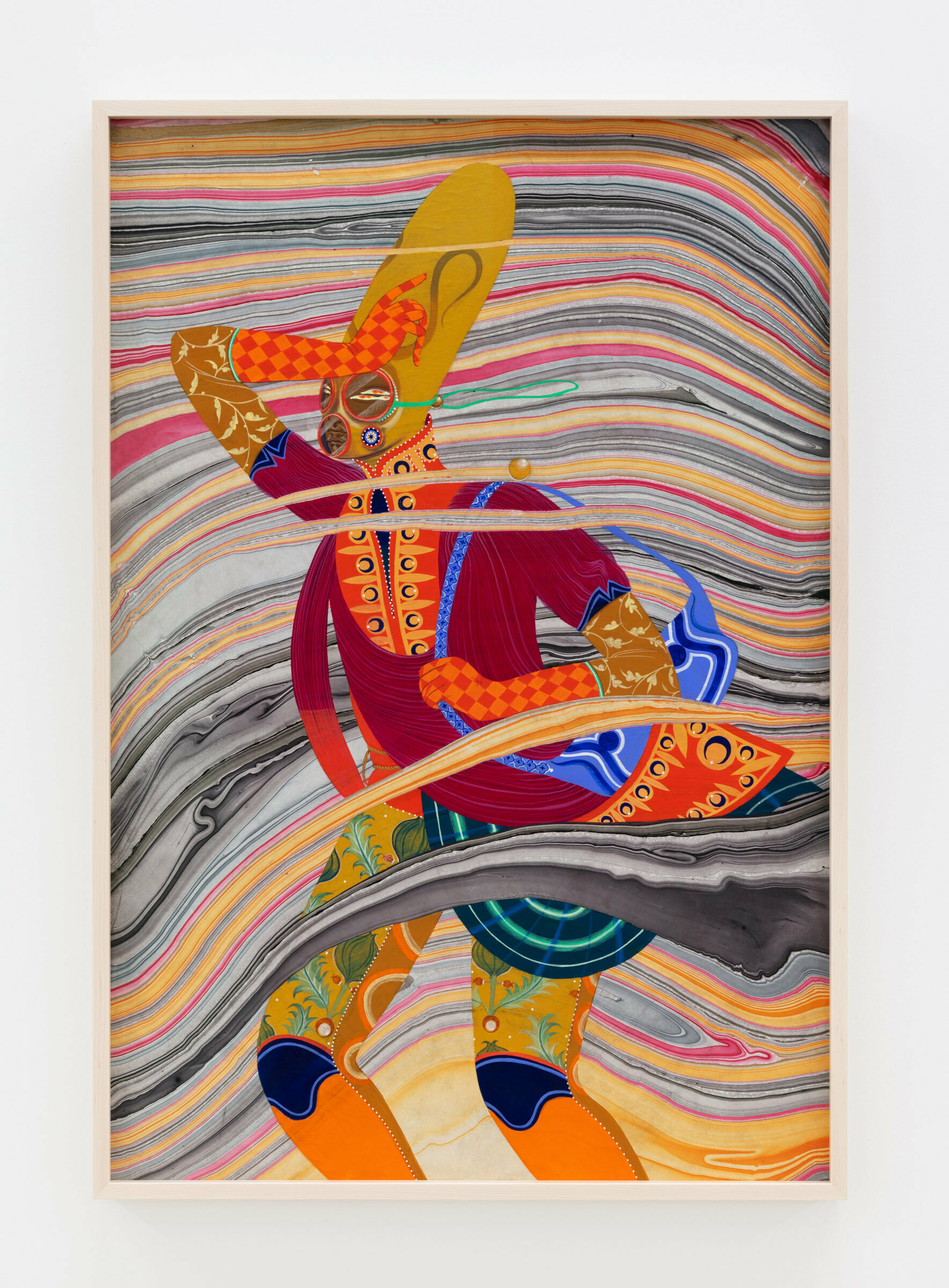

RE: So, Afrika Galaktika had and has its space – to me, it’s like the precursor of the Traveller series, its first instance, an approach of presenting female diasporic bodies in science fictions. Could you talk a bit about the Traveller series, some of which was presented in RELATIONS?

RP: The Traveller series started with this one painting that I did for a show called (m)Otherworld Creates and Destroys Itself as my first solo show with Daven Patel. I was thinking of armour, adornment and protection for us. So that show was so heavily science-fiction in its mood – in its elasticity, not really in a feeling of dystopia but more in a feeling of hyperdimensionionality. Looking at European and American space agencies’ protective wear, considering the dangers of space and travel, I was like “that shit is hideous, first of all – Why? What happened?”. I had Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey in mind – there is another way to look at space wear and space travel wear, and it doesn’t really get revisited or hasn’t been revamped. I can go on a rant on this!

RE: Go for it!

RP: I spend a good amount of time researching STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics), and the public sector is severely underfunded in North America. And unfortunately it’s because the military has lost its interest in science and space technology. War time is normally when they release large amounts of funding for space travel, because those developed technologies inform us and what we discover from them goes to technological advancement in war. So, because there hasn’t been an interest to fundamentally push development of military technology, our space research is suffering. Sadly the acquisition of resources and warmongering seem to be the only reasons governments will push space technology. Not a search for peace or the spirit of discovery, which is at the heart of science itself.

STEM has been so detached from the arts for so long, it’s so compartmentalized, in contrast to the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute that opened up an artist residency and nurtured these exchanges. What about NASA, what about the Canadian Space Program? Where are those cross-field collaborations? Why aren’t they engaging with immigrant artists to look at space travel, looking at what we want from that search and how critical imagination can profit both parties?

This brings me back to shitty ugly space wear. I am influenced by what I grew up looking at: types of weave, dye, garments, jewelry... I research a lot of tribal wear too, and the reasons for a type of armour compared to the environment it functions in and why and how it works. Maybe it’s to shield their eyes from sand because they’re a desert traveller. Maybe it’s to protect skin from humidity and bugs.

So I finally indulged in the idea of mutation, culture and change. Science-fiction is redolent of mutation, and we sci-fi fans really love mutation, because it’s this extreme visible form of change to the human body and it can be so beautiful. But the way it’s talked about by mainstream science is that it’s viewed as an abomination. If you can open your mind and your imagination you can see that it’s like the Fukushima daisies. When the nuclear reactor blew up in Fukushima, all the flowers drawing from the contaminated water had multiple or conjoined centers. When you see something happen to an organism like that, the idea is that is drastically changes to allowsitself to pollinate more fruitfully… and understanding why we are still viewing it as a negative thing. I think about ideas like that, parallel ideas of humans moving around – who gets to move around, what types of culture are being mixed together. What does it look like at the end? Who would win? Is it Caucasians/Europeans who have been coddled by their privilege for decades, or is it resilient people who have the genetics to move forward, past the environmental collapse. What would they look like at that point? How do they dress? Where are they going and where do they end up? Those are the questions that the Traveller asks.

RE: I think there’s something very seductive in the way you rendered it, you could’ve gone more spidery in the eyes, and the restraint and the artistic choices mirror the science-fiction influences. It’s a thing that science-fiction does right: showcasing those mutations as improvements, as positive to the being vs. being viewed as deformed and abnormal.

RP: Yeah, Cheryl was really nice and she described my work as “politicized sensuousness.” In regards to the way that it’s painted, it’s really important to me. I pay attention to it for long enough that that’s the charge that goes to the viewer. It can’t be just the idea, or one type of execution. As you can see, I’m going toward sculpture and different things.

RE: I think that’s something that really translates and transpires. Mostly in the choices of fabrics, like a lot of brocade, and fabrics that feel inspired by South Asian fabric productions. I wanted to know a bit more about those choices. At the beginning of the pandemic, we viewed it as a failure or waste of time, and we rapidly witnessed this shift of utilizing this time to learn useful skill sets like gardening, mask making… For me, I wanted to improve my sewing skills, to learn about pattern making, fabric resourcing and traditional garments. This changed the way I approached your work, from more of a workmanship perspective. I was really interested about the origins of the fabric you painted and the place of relics in your work.

RP: Relics?

RE: When I saw your work last fall in Toronto, I felt like there was a lot of research in the garments, looking at ancestry clothing, in the patterns, and looking at craftsmanship of the jewelry. How they become almost relics of their time and how they sustain and transform their meanings.

RP: Yeah, it’s really funny what we come back, what we come here with, a reverence for makership of the thing we wear to protect ourselves. Fabric for us will work in so many more ways than just a functional garment. I have a hugely invasive and large amount of clothing. The way that I collect it, it has this reverence for fabric, textile, pattern and things like that. I think it’s like special for folks that moved around a little bit more. In a lot of ways the Traveller series is an extension of myself: I have been travelling since I was very small. We were never able to stay in one place for one reason or another. Looking for a better place that’s safer, or escaping bad situations or things like that. So one of the things that I came away with was a reverence for the things that protect you, the garments, the way that you express yourself with your lineage and how you feel about yourself in the world through your clothing.

RE: Yeah, in the paintings they do exude a sense of protection but also a sense of regality through their ornamentation, colouring and patterns.

RP: So a lot of the patterns, I make them up, or it’s a revision of something I remember. I look at the tones of fabric. I don’t know if you have ever been into a fabric store – oh yeah, you’re sewing...

RE: Yeah, my next stop today is the fabric stores.

RP: At Fabric Fabric?

RE: I haven’t been yet!

RP: It’s a huge warehouse! So anyway, stores like that, and when I travel I try to look at what is done locally – the methods of fabrication and the method of fabric production that are dying. In Sri Lanka, we do a lot of handloom, broadloom, cottons and linens that are like specifically patterned and woven. I grew up with an appreciation for that. So I create my own patterns based on all those fibre influences and research. We don’t pay attention to the things that we put on our bodies. The more time that is spent on a piece of clothing that you are wearing… I feel like that’s almost a magical charge that you put on yourself.

RE: I agree. I’ve always been attracted to fabric and texture. I’m the weirdo that shops for clothing based on touching, not on looking.

RP: Yah! You’re supposed to put it on your body. You can feel it all the time, it’s not a joke.

RE: I’ve always been that way. And now, cause I’m starting my MFA, and questioning myself: why this sudden forward interest in fabric? So I’m looking at my own heritage, because I’ve never really done that. I’ve always dissociated from that during my BFA, because I was trying so hard to not be categorized as a diasporic artist.

RP: I know, that’s completely your right!

RE: I didn’t want to be limited by Moroccan heritage. I’m addressing it for the first time, and looking at traditional North African fabric, and why it is that way. For example, traditional Berber wedding garments contain a lot of layering, because of the economic status of fabric but also to protect from the sand and particles, cause it’s the desert.

RP: Totally, it’s the desert.

RE: So it got me wondering about your work, with this new knowledge.

RP: Yeah, there’s a good mix of survivalist gear and creative fanciful, imaginative couture wear – the type of clothing that I’ve seen from travelling, and the types of textiles that I’ve had the honour of touching. I realize that it is a privileged position to be able to save money and move around to see different things like that. That’s something that I’ve been so lucky to do. That plays into my work in a huge way, especially when I get to talk about an evolved immigrant superhuman.

RE: Cool! I’ve been following your newer work on Instagram, and I really like the direction of your work now. To me, it is a follow-up to the Traveller series. The two works that we have at the PHI Foundation show those characters indoors. Now, with the marble paper, it feels like the outside, a view of this futuristic environmental state. We get to see the garment in action, in contrast to the more poised poses of the works we are presenting.

RP: Yeah they seem more stiff and posed.

RE: Yeah, a kind of aristocracy. I really love seeing them in movement, in action and protecting those beings in these newer works.

I have one last question for you. You are inspired by science-fiction and ancient technologies, and science-fiction often takes place in the future, and not necessarily in space. I wanted to know what elements of the present you would consider as artifacts or what would withstand in those future diversities.

RP: There is an element of artifactual objecthood that comes into play here. It also has to do with my complicated relationship with institutions of categorization and archiving, like museums.

RE: Haha ok!

RP: I really like to explore the weird relationship that I have with museums: reverence and appreciation for them, and also the display and theft of objects that, in the place of their origin, are fully active and living objects that are in use day to day – which is something of the way I like to show it in my exhibitions. These objects that I made honestly come straight out of the paintings in a lot of the cases. Sometimes I like to display it as though they were artifacts in a museum. It perplexes me, even. There’s something about when I show it and I think: now it is complete – you know what I’m saying? But in the painting, it shows almost like a recorded future.

RE: Aww, I like that wording!

RP: The way that it comes like “Yeah, it looks good,” but every time I do that type of display, it’s my weird pull into museums and how much I love them. It’s a really strange and tearing relationship that I have with the visual language of categorization and ethnography. It’s like taking a seashell out of the water, and drying it in a box, all the magic goes out of the seashell. In the paintings, when I painted that ring for truth, that long ring...

RE: Yeah, I remember.

RP: So that showed up in a painting with a woman with eyes the same colour who can pull the truth out of liars.

RE: You also displayed them as physical objects.

RP: So I cast them in brass, and I wanted to put them on a cushion. That made me think about the empire and imperial rule. Maybe there is a terrible part about the Traveller’s world too that I don’t know. I have yet to depict those things, the politics of the Traveller’s world. Now, I’m just looking at a way to talk about immigrants as being the survivors, the victors of the future on this planet of others.

RE: I’m very curious about that. Would it change their status as immigrants?

RP: Mmm yeah, I don’t know. What if some people evolve in one direction – say a part of the world where there’s no more sun because they’ve polluted it so much that there’s no light. They would look very different from the people who’ve been evolving in a sunny desert place. Would they still be considered human? A lot of it has to do with evolution, inclusivity, exclusivity and end result. What comes out the other end? Politics or not? Justice or not? The status of being an immigrant when it becomes the majority, because the oppressors are dead, because they couldn’t survive. I’m hopeful that it would then become a fair and just world, and we have a chance again. Even with this pandemic, we are talking about a second chance. I don’t really know.

RE: I don’t know.

RP: I hope so!

RE: I feel like the good thing that came out of this pandemic is an awareness, since we were all placed in the same status quo of being at home and all on our social media. It brought up an awareness of how broken the system was and is.

RP: It made us focus.

RE: Yeah, I think it’s good. I think that’s the best thing that came out of it. It’s just how...

RP: Yeah, how much of a wake up call.

RE: Yes! It’s realizing how completely compliant we are with the system without questioning it. Like participating is now an act of resilience. Wanting to understand what is happening and how we can change it...

RP: I feel like it’s not just the virus that’s come under the microscope.

RE: Which I think is a good thing. I hope this level of accountability will sustain itself.

RP: I think we can all kinda make sure of that. Remedy people’s really low attention spans. We are not good at staying on task, and I feel like we were forced to do some of that now – and realizing, “uh-oh.” It’s funny that you mention that we are looking at the same reality. We spend a lot of time on our phones now. But the looming issues of our civilization are so large that it all seeps straight into this... distraction. Black Lives Matter and the way that it blew up from a tragic event. It’s a flowering and blossoming movement. It’s at the centre of what needs sustained thought and action, as it has always needed to be

RE: Yes, it questions the functionality of equity. We are learning that it’s not the solution, because it assumes that we are equal, and we are not. It’s compromising our privileges to be able to aid and balance the scale.

RP: Bringing all our privileges to our face. It’s the best way to have a better grip on now.

RE: I do hope that this withstands.

RP: That’s what I say to my daughter. We have to make it, there’s no hope, we don’t have a choice but to push forward the world we need.

RE: Aw... thank you, I feel like this is the best way to end this conversation. Thank you again, Rajni.

RP: My pleasure, and thank you for this exchange.

Rajni Perera explores issues of hybridity, sacrilege, irreverence, the indexical sciences, ethnography, gender, sexuality, popular culture, deities, monsters and dream worlds. All of these themes come together in a newly objectified realm of mythical symbioses. They are flattened on the medium and made to act as a personal record of impossible discoveries. In her work, Perera seeks to open and reveal the dynamism of these scripturally existent, self-invented and externally defined icons. She creates a subversive aesthetic that counteracts antiquated, oppressive discourses and acts as a restorative force through which people can shift outdated, repressive modes of being and reclaim their power. rajniperera.com

This article was written as part of Platform. Platform is an initiative created and driven jointly by the PHI Foundation’s education, curatorial and Visitor Experience teams. Through varied research, creation and mediation activities in which they are invited to explore their own voices and interests, Platform fosters exchanges while acknowledging the Visitor Experience team members’ expertise.

Author: Rihab Essayh

Born in Casablanca, Morocco, Rihab Essayh obtained her BFA in studio arts and art education at Concordia University in 2017 and is currently pursuing her MFA in studio arts at the University of Guelph. Essayh is a multidisciplinary artist with an auto-ethnography documentation process that is transformed through a research-based methodology aimed at basing and referencing the current state of cultural anthropology. Employing an immersive approach, her installation artworks serve a contemplative gaze of contemporary interpersonal issues. Her works have been presented at Never Apart, Conseil des arts de Montréal, Fofa Gallery and Art Souterrain festival.rihabessayh.com

Foundation

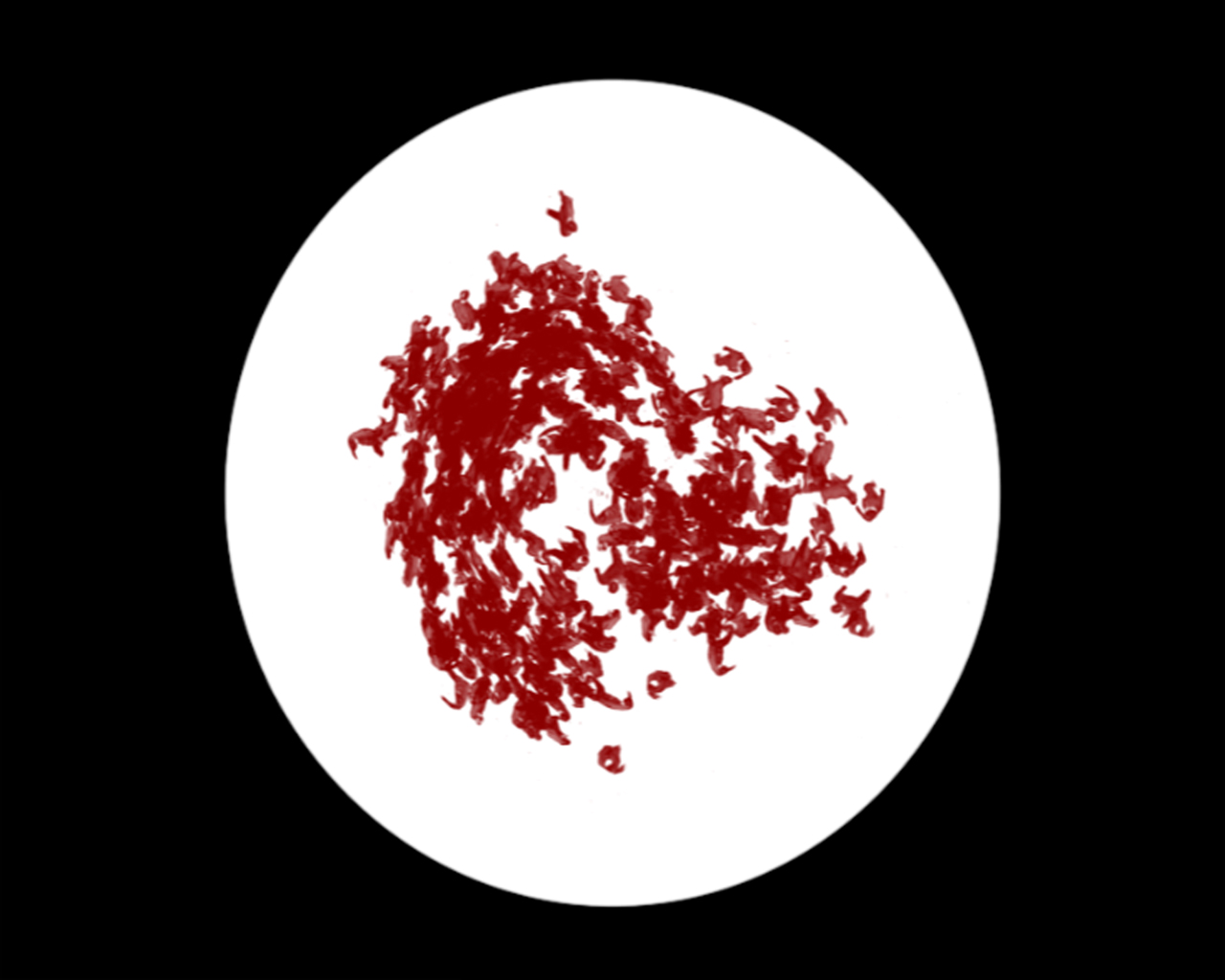

Gathering over forty recent works, DHC/ART’s inaugural exhibition by conceptual artist Marc Quinn is the largest ever mounted in North America and the artist’s first solo show in Canada

Foundation

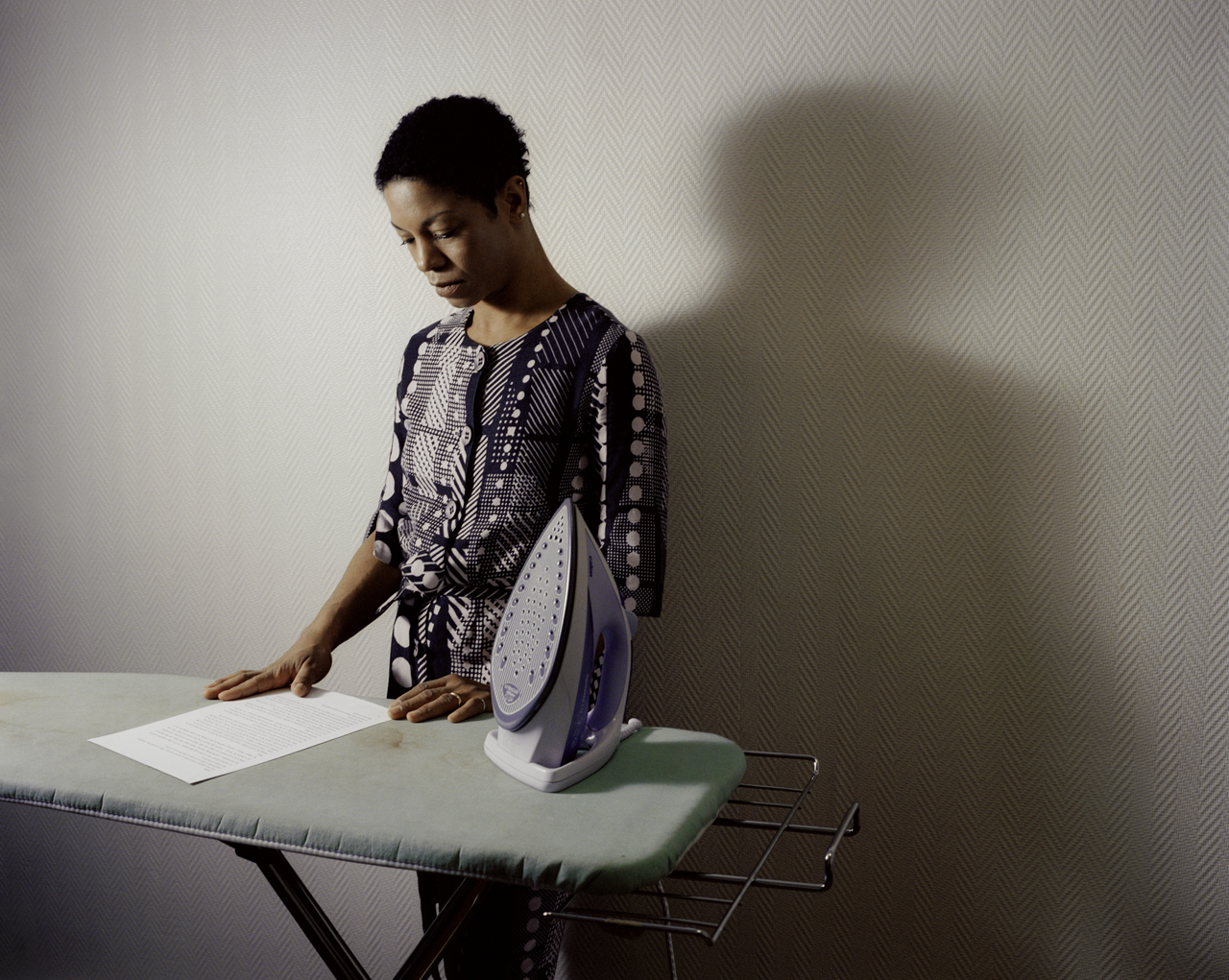

Six artists present works that in some way critically re-stage films, media spectacles, popular culture and, in one case, private moments of daily life

Foundation

This poetic and often touching project speaks to us all about our relation to the loved one

Foundation

DHC/ART Foundation for Contemporary Art is pleased to present the North American premiere of Christian Marclay’s Replay, a major exhibition gathering works in video by the internationally acclaimed artist

Foundation

DHC/ART is pleased to present Particles of Reality, the first solo exhibition in Canada of the celebrated Israeli artist Michal Rovner, who divides her time between New York City and a farm in Israel

Foundation

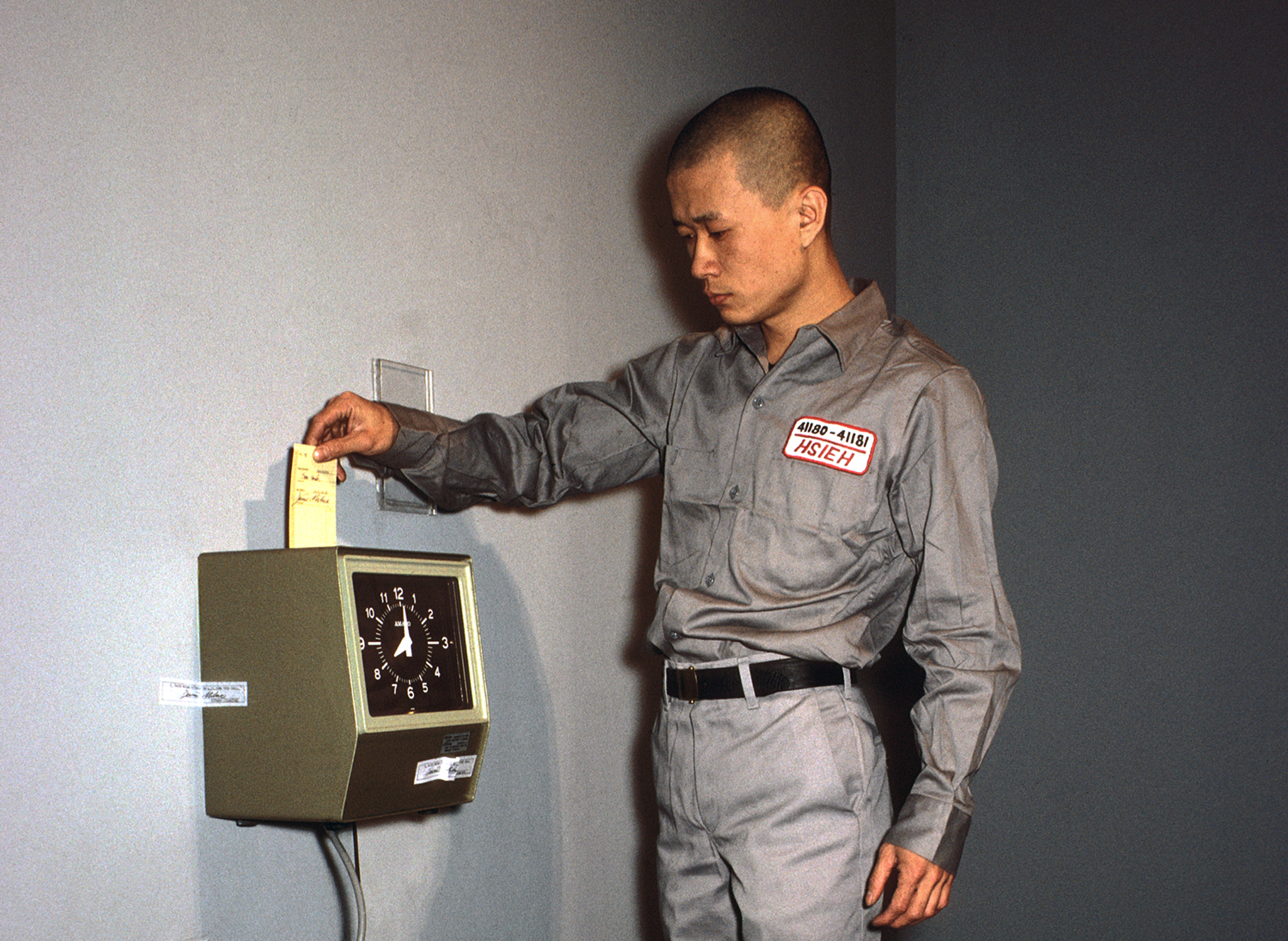

The inaugural DHC Session exhibition, Living Time, brings together selected documentation of renowned Taiwanese-American performance artist Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performances and the films of young Dutch artist, Guido van der Werve

Foundation

Eija-Liisa Ahtila’s film installations experiment with narrative storytelling, creating extraordinary tales out of ordinary human experiences

Foundation

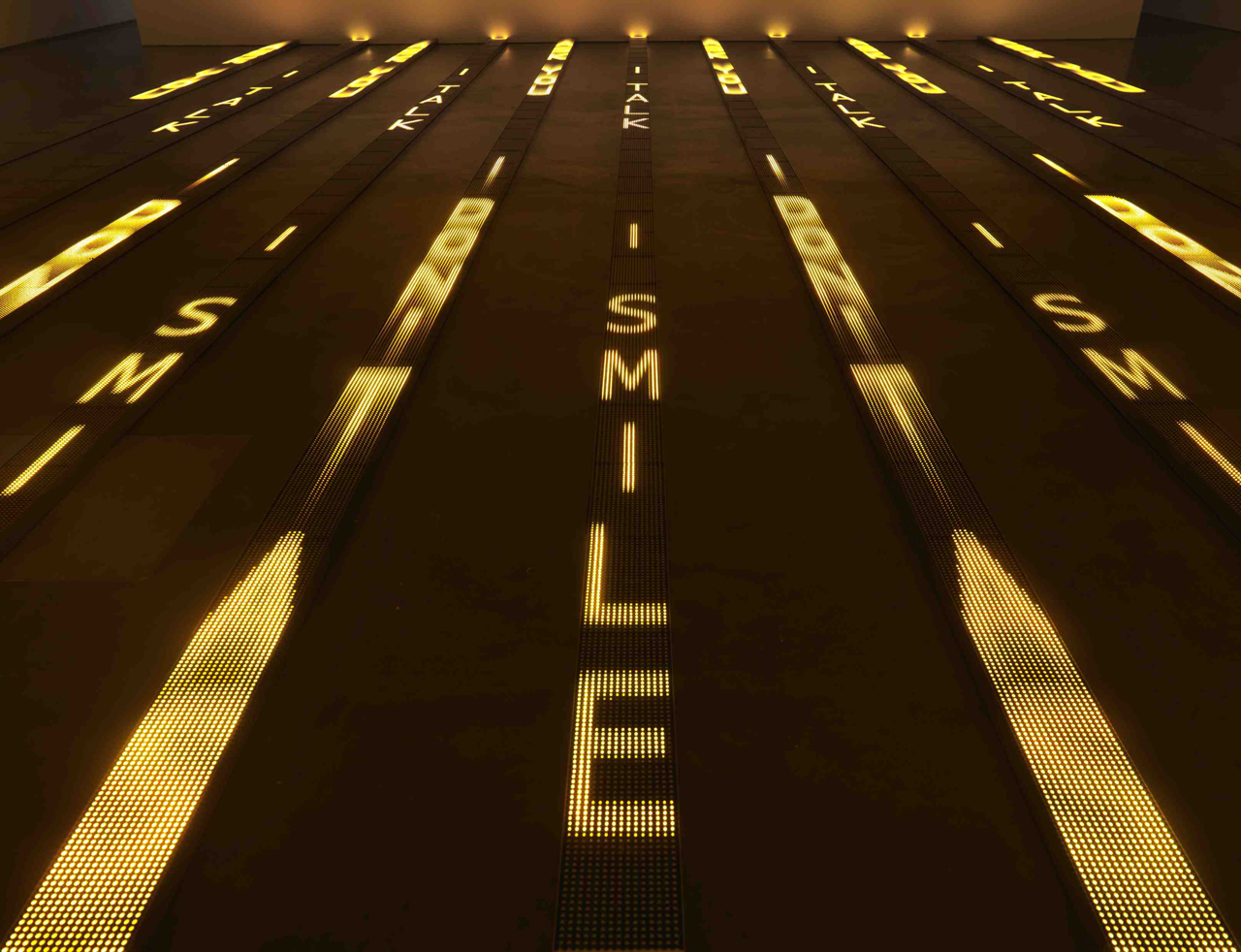

For more than thirty years, Jenny Holzer’s work has paired text and installation to examine personal and social realities